The shocking real-life crime spree that inspired the Luminaries

6-7 minute read

By Alex Cox | July 6, 2020

Is BBC's The Luminaries based on a true story? We delved into our records and newspaper archives to find out more about New Zealand's gold rush.

TV drama The Luminaries tells an epic story of love, murder and magic in the goldfields of 19th-century New Zealand. The TV series is based on a book of the same name but how much of both stem from the facts of history?

To find out what life was really like on New Zealand's West Coast during the gold rush, we dug deep into our records and archives. What we discovered is one of the most shocking stories of gang brutality in New Zealand's history.

The Burgess gang was a rabble of thugs that terrorised the developing communities around New Zealand's South Island gold mines during the 1860s. And just like the tales told in The Luminaries, the gang's incredible story is one of murder, betrayal and defiance.

New Zealand's west coast gold rush

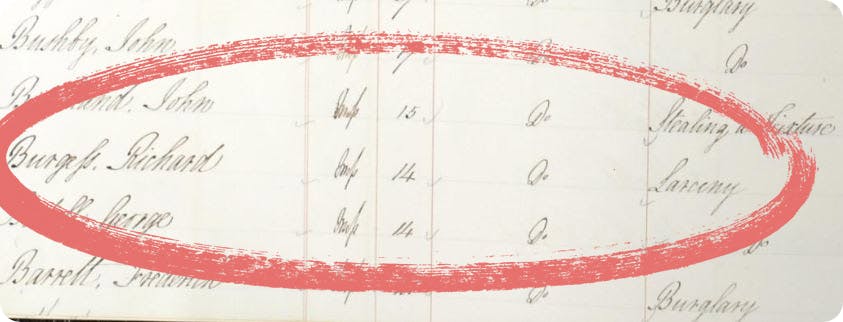

After gold was first found near the Taramakau River in 1864 by two Māori men, the gold rush that followed quickly populated the South Island’s West Coast which, up until then, had been visited by few Europeans. Miners were attracted from the Central Otago Gold Rush and from Victoria, Australia where the gold rush had nearly finished. By the end of 1864, there were an estimated 1,800 prospectors on the West Coast, with many in the Hokitika area.

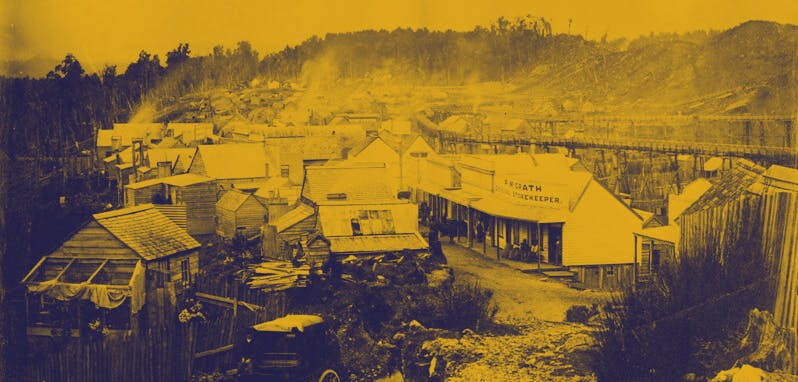

Hokitika Township, circa. 1870.

By 1866, Hokitika was the most populous settlement in New Zealand with a population of more than 25,000 and more than 100 pubs. This burgeoning society is the setting for the drama that's been entertaining audiences in The Luminaries.

Richard Burgess and the Burgess gang

Richard Burgess may be the most prolific murderer New Zealand has ever seen. It’s estimated the death toll his gang of outlaws inflicted while roving the goldfields of the South Island in the 1860s ranged from at least five to anywhere up to 35 people.

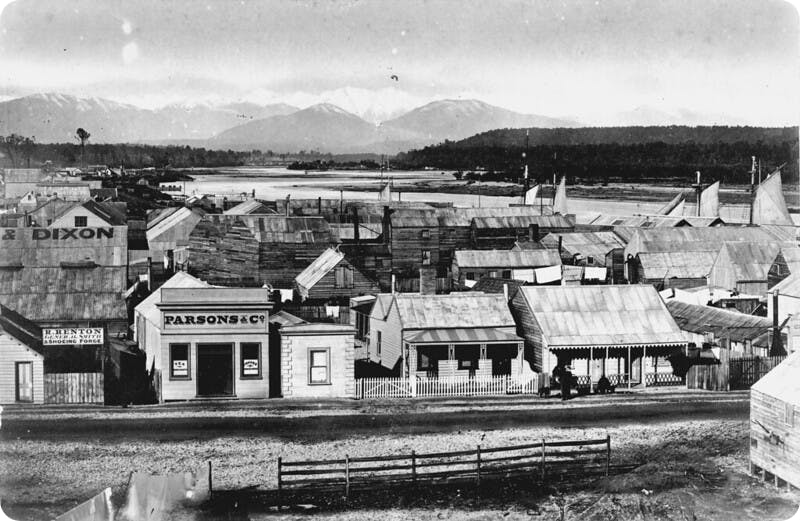

The Burgess Gang, Illustrated Times, 29 September 1866.

He sealed his place in New Zealand's history with a 46-page confession. Mark Twain described the confessions as;

"“without peer in the literature of murder” "

The Burgess gang is best known for the so-called Maungatapu murders, crimes which saw all but one of the gang hanged. The lone survivor was Joseph Sullivan, who turned traitor to save his skin.

The life and times of Richard Burgess

The gang's leader Richard Burgess, also known as Richard Hill, was born in London’s Hatton Garden in 1829, the illegitimate son of a lady's maid and 'someone connected with the Horse-guards'. When his father disappeared, Richard and his mother moved to the East End where he joined a gang of petty thieves called the 'City Arabs' at the age of 14. He was soon imprisoned and flogged for pickpocketing.

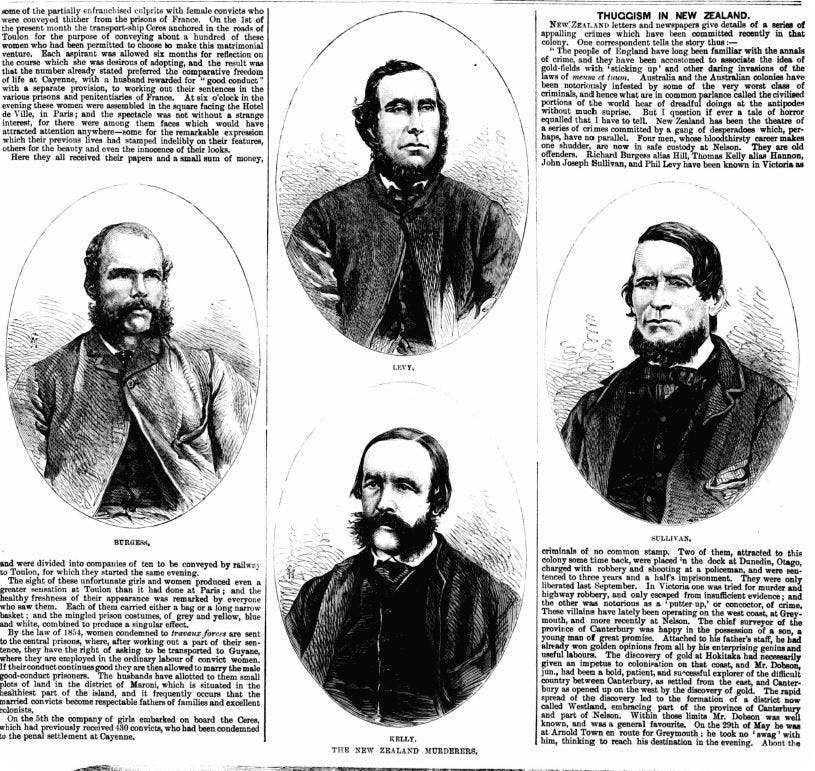

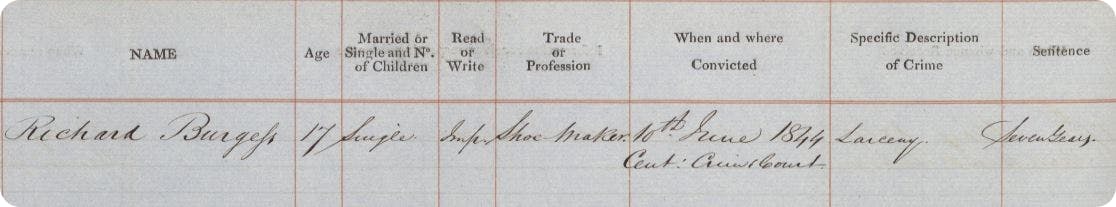

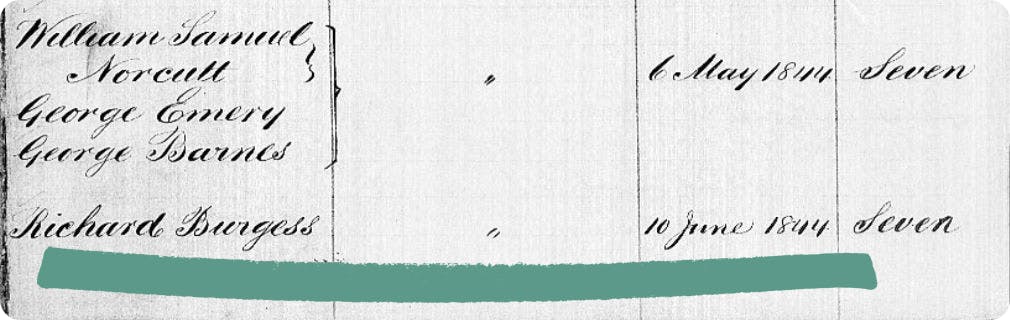

Burgess is listed in England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment, 1770-1935 for theft, aged just 14.

By the age of 16, he had graduated to housebreaking and was sentenced to 15 years' transportation. After 20 months' solitary confinement he was shipped to Melbourne, arriving in September 1847. He was eventually released but barred from returning to England so took up work as a stonemason and assumed the name Dick Hill.

A note on one of Burgess' crime records says his conduct is "very bad". View the full record.

Described as a “smart dapper little fellow, 5 feet and 4½ inches, fresh complexion, brown hair, hazel eyes”, Burgess roved the goldfields of Melbourne robbing miners as part of a gang and soon became a wanted man.

Burgess was transported on The Marion to Australia. His record entry can be found in Convict Transportation Registers 1787-1870.

In 1852, he was sentenced to 10 years in the brutal Melbourne gaol and the prison hulks. He twice tried to escape from those 'floating hells of misery', the second time in an 1856 bid led by the infamous bushranger 'Captain Melville' (Frank McCullum). Three people died, including a policeman, but the nine defendants at the murder trial, including Hill, escaped hanging on technicalities.

Some historians have argued that it was the hellish conditions on board the hulks that turned Hill into a monster. Determined never to return at any cost, he decided that from now on he would leave no witnesses. He was finally released in 1859 only to be rearrested again for burglary. He was able to hide his past by using an alias so only received a light sentence. With Australia now deemed too 'hot' for him, he fled to New Zealand.

The gang gathers in New Zealand

In 1862, Burgess headed to the Otago goldfields where he joined forces with various Australian colleagues to prey upon the miners there. Many were former cellmates including his right-hand man Thomas Kelly (alias Noon).

That same year he and Kelly had a shootout with police and were sent down for another three years. Burgess claimed the charges were false and vowed to take revenge on society when he was released.

After a failed escape attempt, Burgess 'was considered the ringleader in every refractory outbreak in Dunedin Gaol and was lashed. He is said to have determined then that he would take a life for every lash received.

The Burgess gang head for Hokitika

Burgess and Kelly were released in 1865 made their way to Hokitika. The local police had insufficient resources to place them under surveillance, so the pair, with others, resumed a roving life of crime on the West Coast goldfields. In the gangs which formed for specific 'jobs', Burgess was always the leader.

Burgess soon formed an alliance with former publican and prizefighter Joseph ('Flash Tom') Sullivan, who had just arrived from Victoria and together, their criminal activities increased.

They then recruited professional 'fence', William (alias Philip) Levy, to dispose of the proceeds of a planned bank robbery at the Buller River.

The Dobson murder

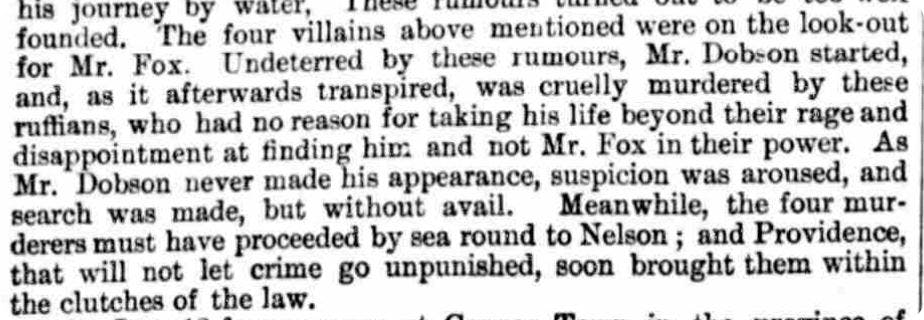

To escape police surveillance, the gang moved north to Greymouth. Two days after their arrival, they held up and strangled a young surveyor, George Dobson, who they had mistaken for gold buyer E. B. Fox.

A graphic account of Dobson's murder appeared in Illustrated Times on 29 September 1866. Read the full article.

George Dobson was the second son of Edward Dobson, a prominent civil engineer who oversaw the construction of much of the country's earliest infrastructure.

The Maungatapu murders

After murdering George Dobson, the gang fled to the declining goldfields in the Buller area in the hopes of robbing the bank there. Unfortunately for them, the bank had closed and they were soon destitute.

They walked the rugged, isolated Maungatapu track to Marlborough. While they were encamped at Canvastown, Levy reconnoitred the Wakamarina goldfield. At Deep Creek, he learnt that an old acquaintance, Felix Mathieu, now a local publican and storekeeper, was about to depart with two other businessmen and a miner to investigate prospects on the West Canterbury goldfields. Burgess had already insisted that the gang should return to Nelson and catch a steamer, as they drew attention to themselves travelling on foot. On the way, he now decided, the party from Deep Creek, which would be carrying money and gold, would be waylaid.

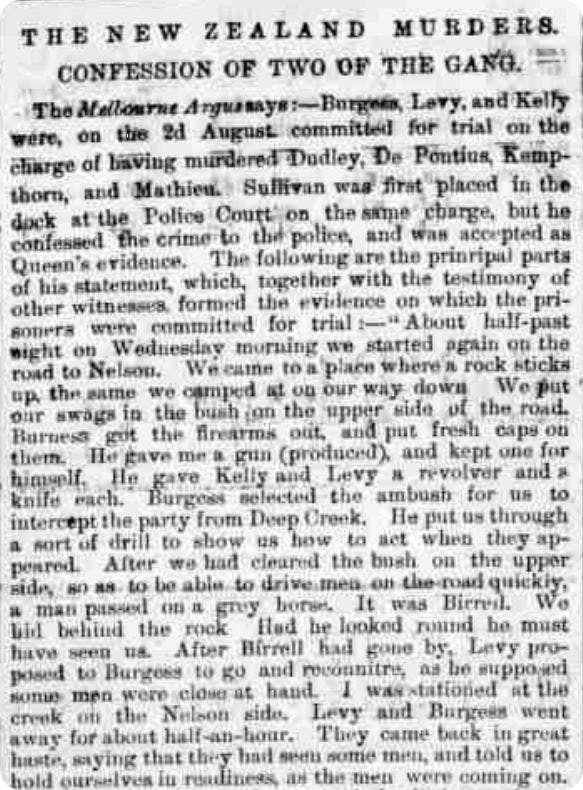

According to Burgess, Kelly refused to participate in any hold-up and Levy was not told about it and that pair travelled on ahead. While in Sullivan's version the whole gang was involved.

En route, they met an old miner, James Battle, who became suspicious of their intentions. He was robbed of his £3 17s, throttled to death by Burgess, and buried.

As planned, the Mathieu party was 'stuck up' and robbed of some £300 in gold dust and notes. To remove all witnesses James Dudley was strangled, Mathieu shot and then knifed, and John Kempthorne and American digger James de Pontius shot. De Pontius was buried so that the police would think if the other bodies were found, that he had murdered his travelling companions and fled.

The Burgess gang gets busted

The murdered travellers were soon missed and a reward was put out. After seeing a poster offering a free pardon for any accomplice not specifically involved in the murders, Sullivan turned his comrades in and directed search parties to the bodies.

Burgess and Kelly represented themselves at trial. Burgess was determined to establish Sullivan as his sole accomplice in the Maungatapu murders and as the murderer of Dobson.

During the trial, he read out for five hours 'The confession of Burgess, the murderer', in which he detailed many crimes and exonerated Kelly, Levy and others implicated by Sullivan. In prison, meanwhile, Burgess had expanded his written 'confessions' into a full autobiography, the publication of which was banned for fear of undermining public morality.

Burgess' lengthy confession was featured in Stonehaven Journal on 18 October 1866. Read the full article.

Burgess, Kelly and Levy became the region's first executions on 5 October 1866. While Levy and Kelly protested their innocence, Burgess was defiant to the end. After cheerfully entering the prison yard, he thanked the various officials in attendance and declared that he had;

""had no more fear of death than he had of going to a wedding.""

He then bounded up the scaffold steps, and choosing the centre rope kissed it, saying that he;

""greeted it as a prelude to heaven.""

Almost immediately after the executions, there was speculation that Burgess might have been telling the truth about the role of Kelly and Levy, and some reluctant admiration that Burgess had deliberately set out to get himself hanged in the cause of 'mateship'.

A prominent phrenologist, A. S. Hamilton, who had visited Burgess's cell, gave a lecture in which he expressed admiration for the man's virtues but pity that;

""so much daring, expertness and ability should have been lost to society by being wrongly directed.""

Few would have disagreed with his declaration that Dick Burgess had;

""no rival, either in the magnitude of his crimes, or in the part he acted in his last hour upon earth.""

Is there a criminal mastermind or thoughtless thug hidden in your past? Sometimes the most shocking family discoveries are also the ones that illuminate your heritage like no others. Explore an extensive archive of crime records to unlock your family's shady history and let us know what you find by tagging us on social media with #FindmypastFeatured. We can't wait to hear what you've discovered.

Related articles recommended for you

The history of the Barrow-in-Furness Shipyard

History Hub

Marking 80 years since D-Day with updates to our World War 2 Allies Collection

What's New?

Who's who on King Charles III's family tree?

Build Your Family Tree