The scandalous Edwardian fake heiress who took the press by storm

6-7 minute read

By Ellie Ayton | February 11, 2022

Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction. The story of fake heiress Anna Delvey has been adapted by Shonda Rhimes for Netflix. But over a century ago, another fraudster hit the headlines. Here’s her story.

We love a real-life scandal. The twists and turns of a thrilling tale like Inventing Anna, based on real events, intrigue us in a way we can’t explain. Similar, perhaps, to finding a jaw-dropping story in our own family trees.

As the Inventing Anna trailer says:

" ‘the story is completely true, except for the parts that are totally made up.’"

Who is Anna Sorokin?

Between 2013 and 2017, Russian-born Anna Sorokin posed as a wealthy German heiress, Anna Delvey, while living in New York. During that time, she managed to defraud hotels, banks and acquaintances out of millions of dollars before being caught. Her story has captivated people around the world and is now the subject of a big-budget Netflix adaptation.

See the Inventing Anna trailer below:

Also featured on a BBC Radio 4 podcast, it got us thinking: have there been any ‘fake heiresses’ in Britain? Did anyone else manage to swindle funds from others to live a life of luxury? As it turns out: yes. We delved into our family history records and historical newspapers to uncover more about one elusive con artist from the Downton Abbey era.

In a bizarre coincidence, we first came across this story by chance. A member of the Findmypast team was researching their parents’ wedding venue, and soon the scandalous story unfolded.

Humble beginnings

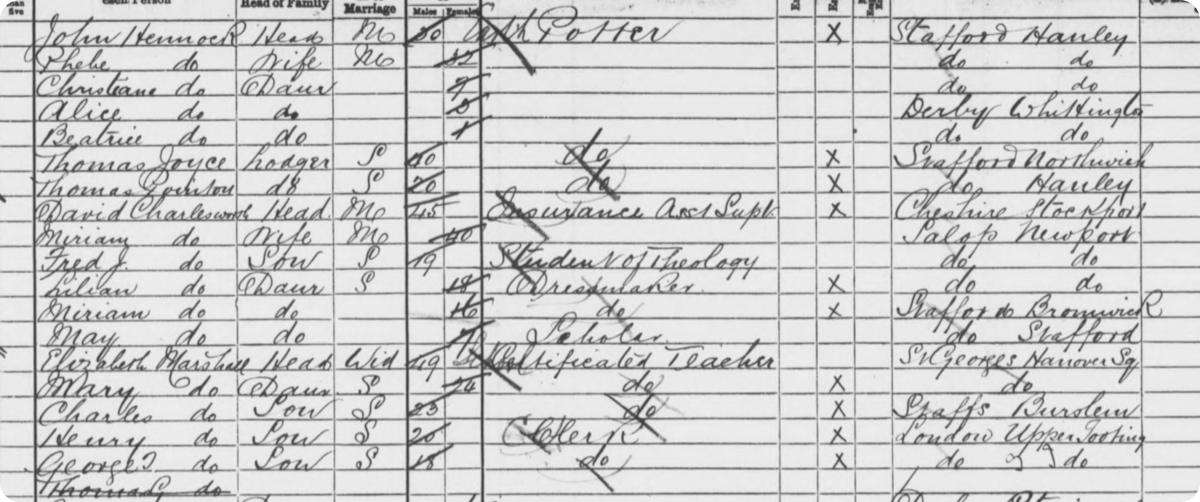

May Charlesworth, aka Violet Charlesworth, was born in Stafford in 1884 to David, an insurance agent, and his wife Miriam Davies. She was the youngest of at least four children. The family lived in and around Derby until the early 1900s when they moved to Rhyl, North Wales.

The Charlesworth family living on King Street, Whittington on the 1891 Census. Intriguingly, Lilian is listed as a niece on the 1881 Census.

In North Wales, the Charlesworths lived a life of luxury, first living in Rhyl, and later at the Bod Erw manor house in St Asaph. Violet was often seen in the local area in expensive cars and clothes. Her alluring lifestyle captured the attention of the press, who reported on her every move.

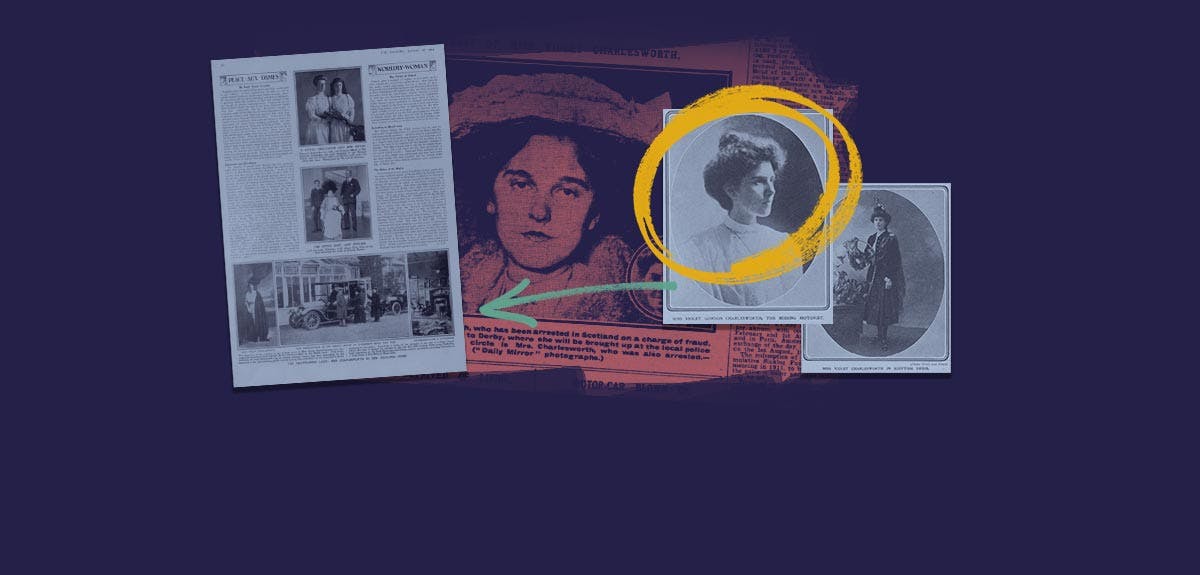

Photos of the ‘heiress’ in The Sketch, 13 January 1909.

In April 1908, she was ‘unavoidably absent’ when her brother opened a bazaar at the St Asaph National School on her behalf. The following month, Violet was out driving and crashed her car into a coat cart when trying to avoid oncoming traffic.

At some point in early 1909, days before Violet’s 25th birthday, there was a terrible accident.

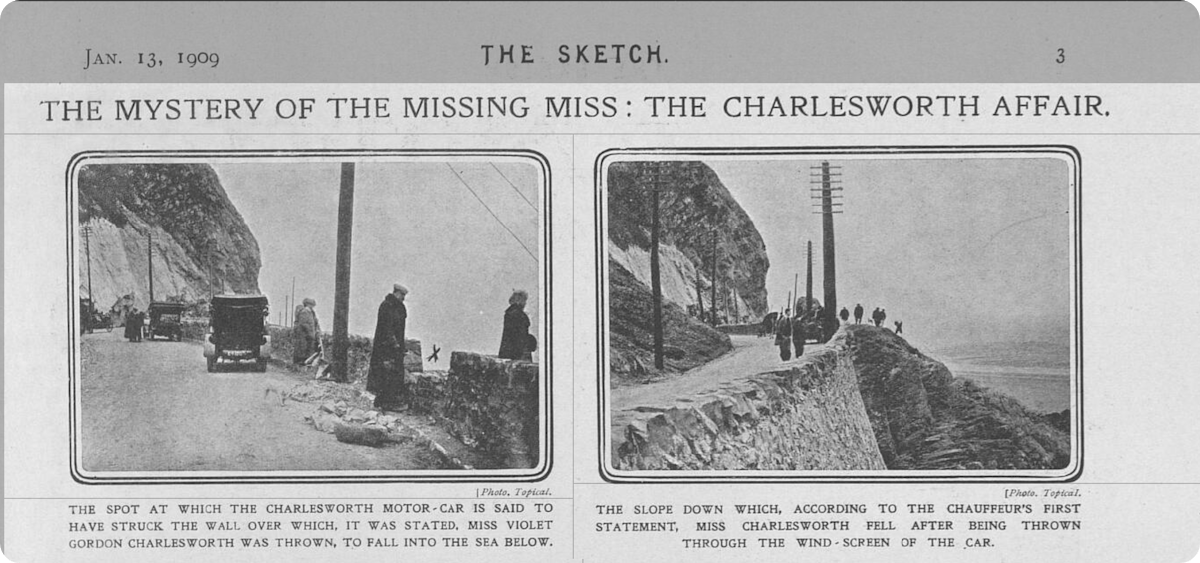

Violet was driving with her sister Lillian and her chauffeur, Watts, along the North Wales coast when an accident occurred. The car swerved and crashed into a wall. Violet was driving at the time, and was reportedly thrown through the windscreen, down a ledge and into the sea. No body was found, and she was presumed dead. To add mystery upon mystery, Lillian is only listed as Violet's sister in their baptism records - in the 1881 Census, they are listed as cousins.

The Sketch, 13 January 1909.

Suspicions around the crash quickly began to arise. Rumours of Violet faking her death to escape creditors circulated, and thus began a nationwide manhunt for the heiress, with descriptions and sightings doing the rounds in the newspapers.

A headline from the Denbighshire Free Press, 23 January 1909.

After an investigation, a young lady by the name of Margaret MacLeod was spotted in a hotel in Oban, Scotland, with a startling resemblance to the dead heiress. And as luck would have it, staying at the same hotel was Mrs Lilian Coulson, Violet’s sister.

Letters written by Miss MacLeod were compared with those of Violet, and the handwriting was found to be remarkably similar.

Dundee Courier, 12 January 1909.

Margaret denied the claims, and interestingly, Lilian denied that Miss MacLeod was her sister entirely. However, after being interviewed in Oban, they travelled together to Glasgow by train, and despite apparently being strangers, they went on to share a room at The Central Station Hotel. Reporters followed them everywhere in Glasgow, and upon check-out, the two ladies escaped them by using the goods lift. But one wily Daily Mail journalist managed to intercept them.

By the time Margaret arrived in Edinburgh, under the care of the reporter, she’d confessed: she was the missing, fraudulent heiress.

"“Yes, I am Violet Charlesworth.”"

The journalist interviewed her about her life and exploits. Violet mentioned that her father had gone to America alone some years earlier. She was the youngest of eight children, some of whom died in infancy.

During the accident, Violet said she became separated from Lilian and Watts:

"“I gave one wild look around, and then an impulse came into my head to get away from the horrible associations of the place.”"

From there, she walked alone to Conwy Station, travelled to Crewe, and onwards to Glasgow. The full interview was published in newspapers across the country, readers desperate for the latest scoop on the story.

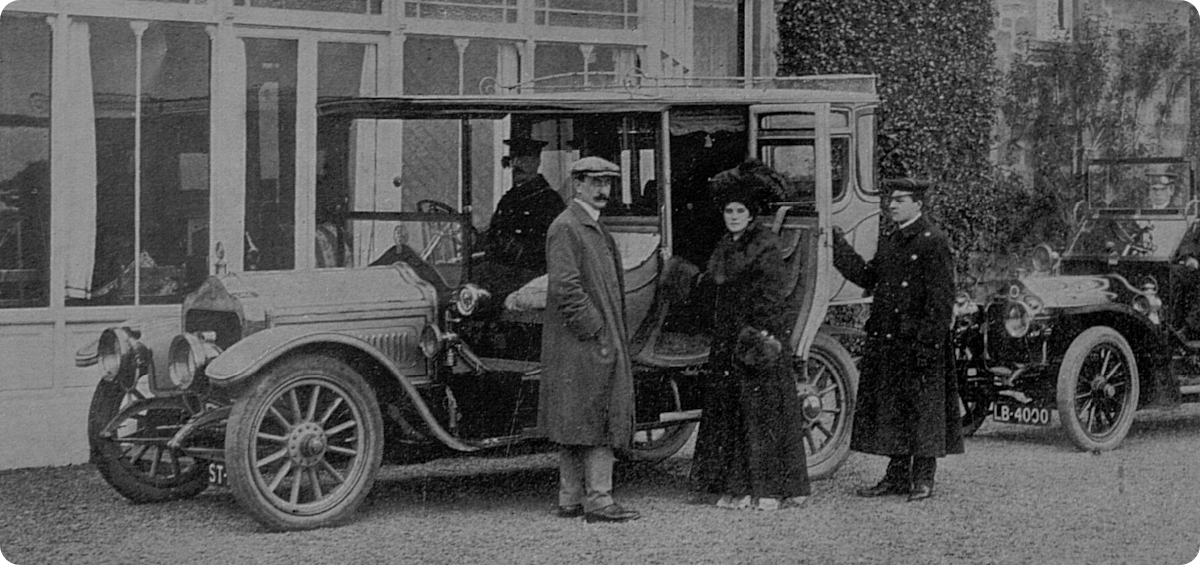

Violet had a love of motorcars. Some of the funds she swindled posing as an heiress went into buying cars. Pictured here at Flowerburn House, Fort Ross, in The Graphic, 16 January 1909: the wider article mentioned the romances young, wealthy ladies had with their chauffeurs.

Soon after, the full extent of Violet's deception was publicised. On 13 March 1909, the Dundee Courier reported debts from the London Bankruptcy Courts. Violet owed sums in the region of £17,000 - over £1.3million today. Previously in her interview, she stated her income came from friends, gifts and an allowance.

It became apparent that her mother, Miriam Charlesworth, told anyone who would listen that her daughter was due to receive a fortune of some £70,000 from a deceased soldier fiancé.

Through posing as an heiress, Violet obtained £5,000 from a Rhyl doctor, Edward Hughes Jones, whom Violet had promised to marry. She told him she would receive £100,000 when she turned 25. £400 was obtained from the widowed Mrs Smith of Derby: her entire life savings. One letter from Violet to Edward, brought as evidence, read;

"“You ken well all my fortune, when I get it, will be yours as much as mine. It cuts me to the heart to ask you for money. I who will have £7,000 a year and an estate, it is cruel, bitterly cruel, but it is all for love's sake, laddie, laddie. And now, Eddie, my own, ever your devoted and some day wife, Violet.”"

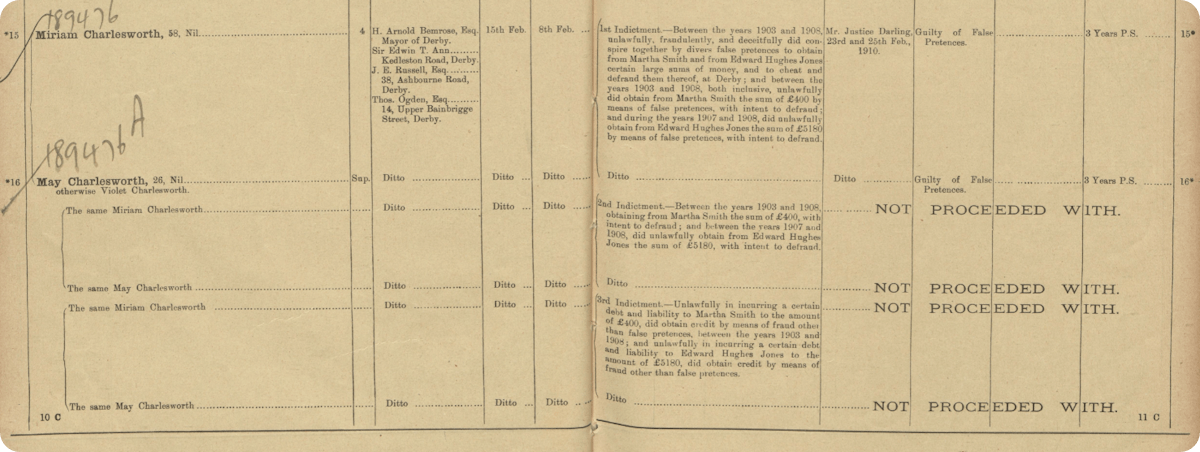

In February 1910, Violet and Miriam pleaded not guilty to fraud at the Derbyshire Assizes. They were found guilty of conspiracy, fraud and false pretences, and sentenced to five years penal servitude. This was later reduced to three years.

Manchester Courier, 25 February 1910.

From the fraudulently obtained funds, Violet had lived a life of luxury, with rented properties in Wiltshire and Scotland, motor cars and several operations on the Stock Exchange.

Miriam and May ‘Violet’ Charlesworth in our crime records, February 1910.

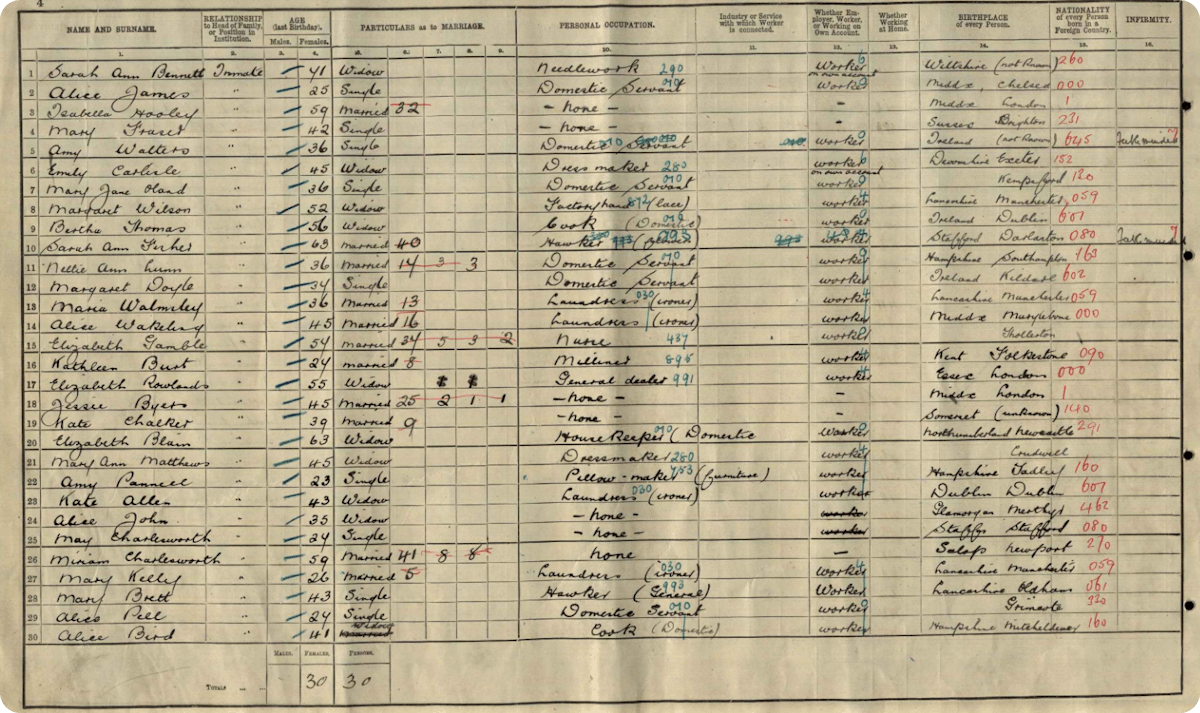

Violet and her mother spent three years serving their sentence in Aylesbury Prison. They were enumerated there on the 1911 Census.

Violet and Miriam on the 1911 Census of England and Wales in prison. You can view the full record here.

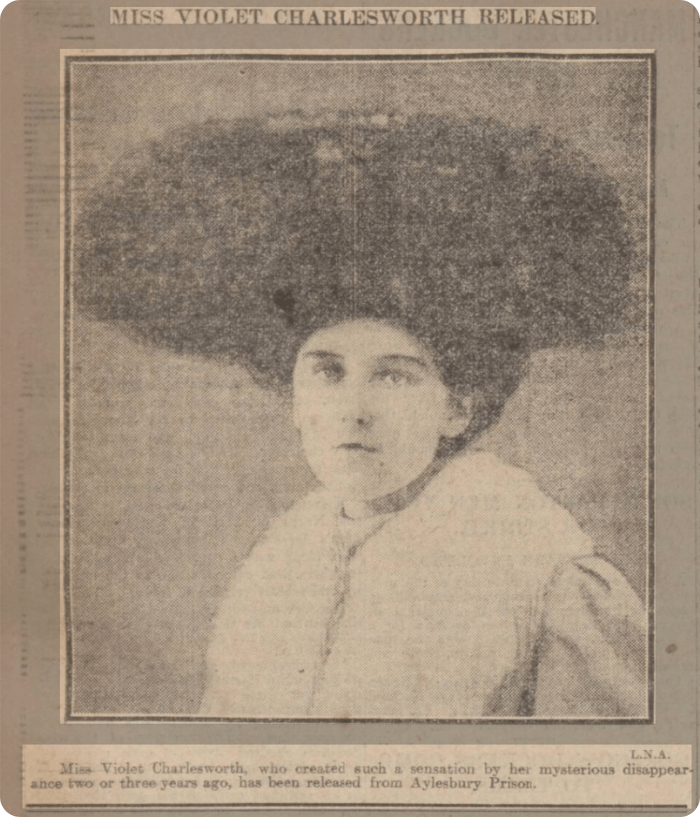

Dundee Courier, 12 February 1912.

In 1912 they were released, and Violet hit the headlines once again.

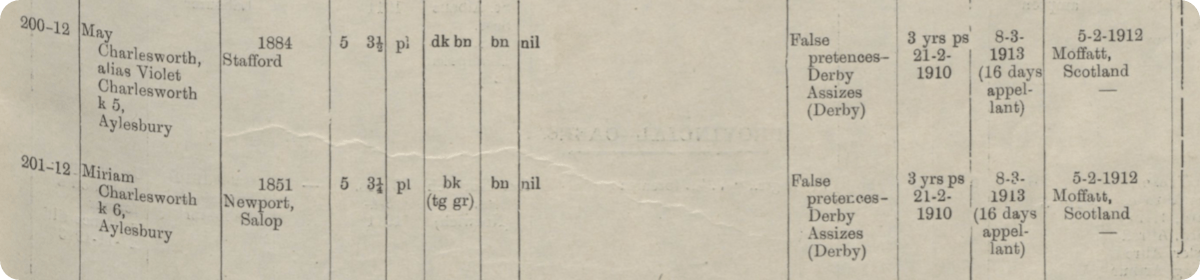

A further crime record, showing their release in 1912 to Moffat, Scotland.

What happened next remains a mystery. After being released, Violet and Miriam fled to Scotland. She may have taken on another alias. Perhaps she married or emigrated?

We believe Miriam died in Lancashire in 1920. There is a death record for a May Charlesworth in Stoke on Trent in 1957. Violet’s brother Frederick was visiting the Goodwill family in Coventry on the night of the 1921 Census.

Perhaps you can take to our family history records and solve the mystery. Be sure to share your findings with us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

Related articles recommended for you

'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

History Hub

The Women's Prize Trust announces Findmypast as the inaugural sponsor of the Women's Prize for Non-Fiction

The Findmypast Community

More footballers in the family? Jack Grealish’s family tree

Discoveries