What was life like on board an emigrant ship generations ago?

3-4 minute read

By Ellie Ayton | September 9, 2020

So, you've found a globetrotting ancestor on a passenger list, or arriving in a new country. But what did they actually experience during their journey?

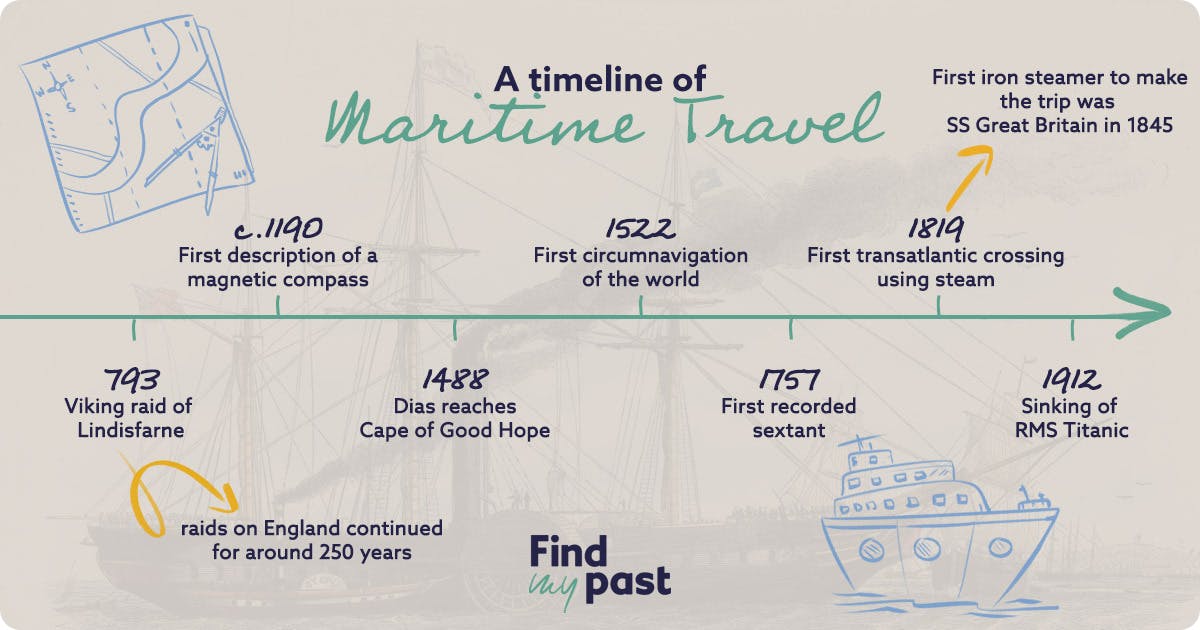

Before the age of aircraft, maritime travel was the main way your ancestors could move around the world. Crossing an ocean for a new home was no mean feat. It could take some weeks and it was often dangerous.

Yet, travel and migration records are key sources for everyone's family history. Read on for what life was really like aboard a passenger ship.

Early migration

Sea travel during the 1600s was long and often unpleasant. When the Pilgrims sailed on the Mayflower in 1620, conditions aboard were cramped and seasickness was rife, as the crossing took place during the Atlantic storm season. Passengers shared the space with livestock and other cargo. The sailing predated steam travel, so the journey took two months. Sitting beside Bessie the cow for 60 days might not have been fun for your ancestor.

In the 18th century, it wasn’t uncommon for ship owners to encourage as many migrants to come aboard as possible so they could maximise the profits they received from a voyage. Conditions were cramped and often unsanitary. It wasn’t until the 1803 Passenger Vessel Act that occupancy was limited in a bid to prevent overcrowding.

The steam revolution

The introduction of steam power in the 19th century meant more voyages across the vast oceans and more chances for your ancestors to make a new life for themselves in a new world. Most would have packed their belongings into a trunk (which went in the ship’s hold and likely wasn’t accessible for most of the trip) and a canvas bag with the essentials for the voyage.

At this time, it typically took 4 months to sail from Britain to Australia and 6 weeks to the United States. That’s a long time to be at sea, although a faster clipper could make the trip in half the time. The time aboard often depended on the size of the ship, the number of sails, the time of year, the weather and the cargo.

Passengers were organised while on board, based on the price paid for a ticket. Those in steerage class (the cheapest ticket, with accommodation in the lower deck of the ship, where cargo was stored) second and third class would cook their own food, and they were divided into messes. This meant that each mess would cook, eat and draw rations together. Steerage passengers would also have to clean their own berths.

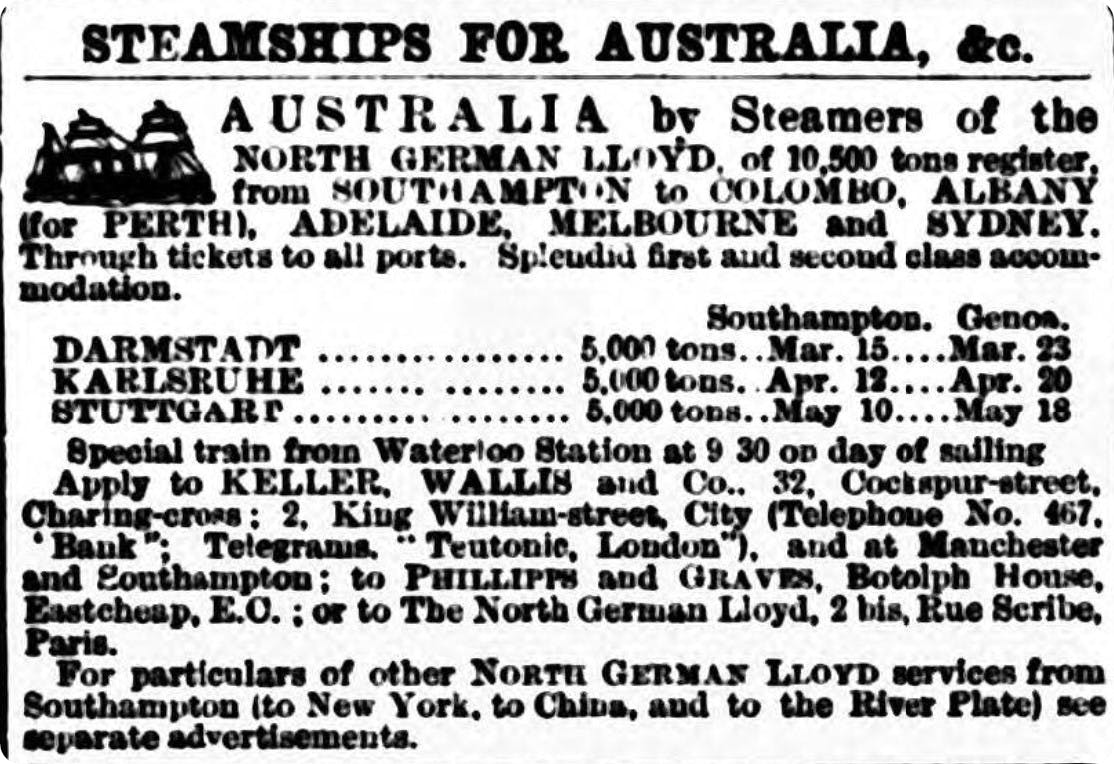

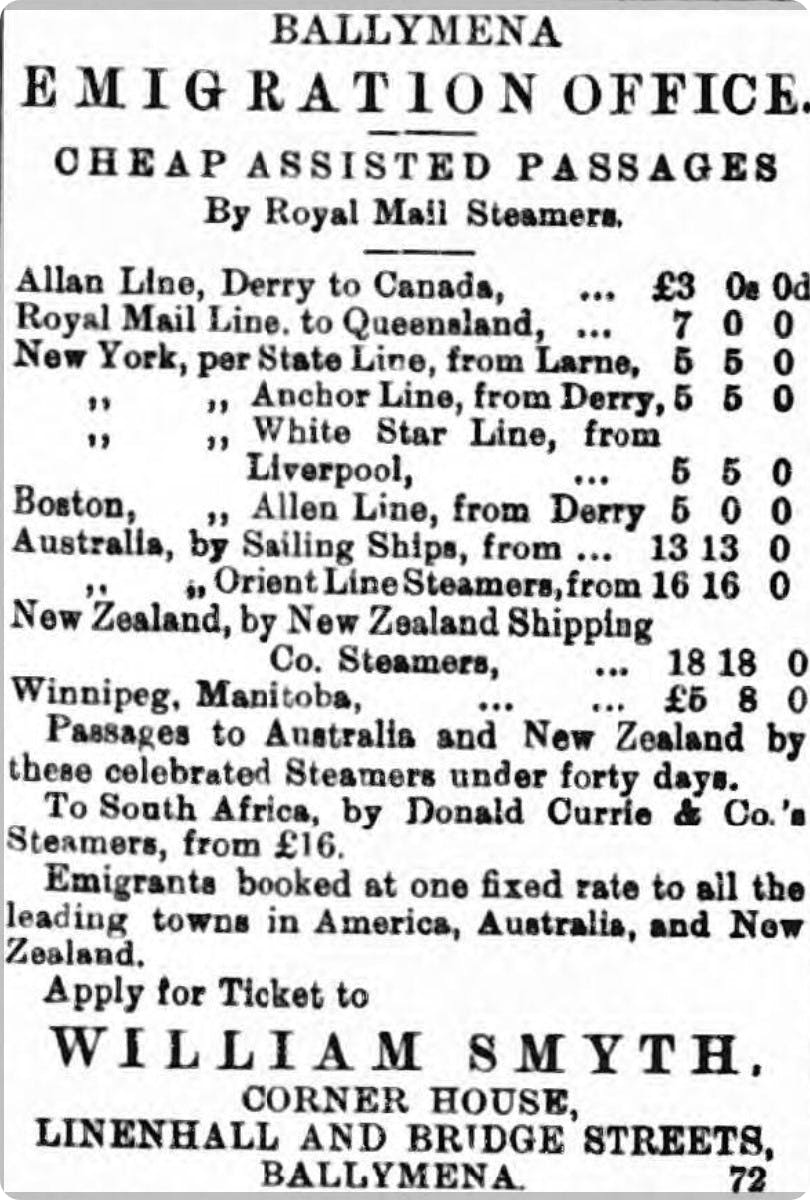

Later, it was common for shipping companies to advertise cheaper passage aboard the regular mail steamers in various newspapers.

Ballymena Observer, 3 May 1884.

If your ancestor was a single woman, she would sleep in quarters with other single women, kept away from any single men, and often supervised. As seen in a diary from 1850, it was considered important to provide;

""more efficient moral and religious supervision.""

This particular diary was published, with the profits for;

""securing the services of Matrons to promote moral and religious welfare of emigrants.""

The author, Reverend John Davies Mereweather, was travelling to Australia.

Day-to-day life on board

A typical day on board was regimented. Passengers were normally out of bed by 7 am, would have lunch at 1 pm, tea at 6 pm, and had to be back in bed for 8 pm. Where eligible, children would attend school during the voyage. Afternoons were normally dedicated to leisure time or catching up on mending or letter writing. Mereweather wrote in his diary;

""The men are in groups, some boxing with gloves; others fencing with foils... the women are sitting on the spars chatting, sowing or knitting.""

Only around 1 in 10 passengers were wealthy enough to afford a cabin. Those in steerage suffered dark quarters and poor ventilation, and in the case of migration to North America, steerage passengers were often European and Chinese migrants.

On his trip to Australia, Mereweather commented;

""As the skuttles are blocked up by the berths and luggage, the whole compartment has a most lugubrious and dungeon-like aspect.""

Further on into the journey he wrote;

""The emigrants complain sadly of the skuttles leaking. Some of their mattresses are saturated with water; consequently they rise in the morning with severe colds.""

The Reverend also wrote about new life, death and disease aboard the ship, detailing the weather and any peculiarities seen during their sailing. These included jellyfish, the scenery, theft, and single emigrants causing trouble, of which he was most interested.

What did your ancestor experience during their journey? Did they keep a diary or send letters? Share their travel tales with us on social media using the tag #FindmypastFeatured.

Related articles recommended for you

Irish family history and minority religions in Ireland

History Hub

'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

History Hub

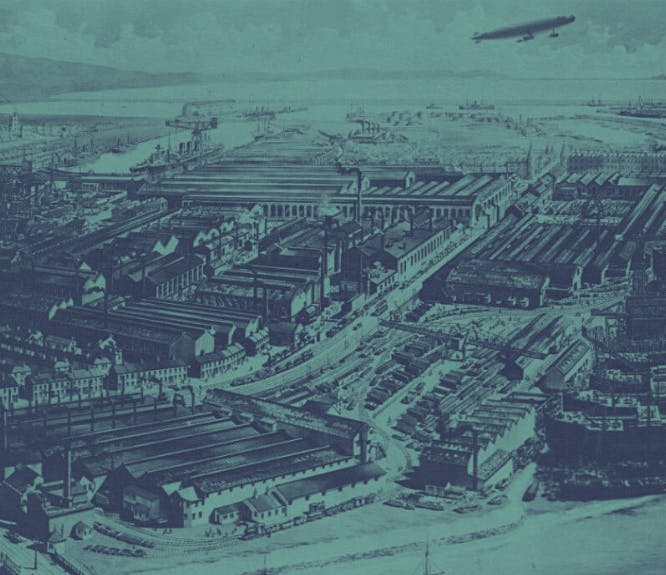

The history of the Barrow-in-Furness Shipyard

History Hub