The Blitz; A first-hand account

6-7 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | September 18, 2015

As part of the 1939 Register project, we've asked those who were there to tell us their stories. Whether it's evacuation, conscription or the FA Cup final, we love reading and sharing accounts of life in the 1930s and during the war.

In this instalment, we hear an incredible and moving first-hand account of the Blitz, submitted by someone who was there. This is Denis' story.

Denis in 1945, after joining the R.A.F.

“I was not quite 14 years old when the Blitz started in 1940, and was living in Peckham, South East London.

The Blitz started in earnest on the 7th of September – I think it was a Saturday, and I had to get to Nunhead railway station to pick up the evening newspapers (I worked in a paper shop). They were thrown from the train onto the platform as it passed through the station.

During an air raid earlier in the day a stick of bombs had hit this area, and houses had been blown down. Dust was everywhere and gas mains in the streets were on fire. Fire engines were everywhere, their hoses across the streets.

Hill Street Peckham after a bombing raid. Image ©London Fire Brigade / Mary Evans Picture Library

Air raid wardens tried to rescue those in bombed-out houses, ambulances had sirens at full blast while police and air raid wardens kept people away from areas which were liable to collapse, or had an unexploded bomb under them. The scenes of destruction - with fire and mayhem – were both frightening and exciting. That night, they came back and bombed the east end of London, around the docks.

From Peckham, we could see the huge, red glow in the sky as the dockland areas with all their stockpiles of sugar, wines, rum, timber and other perishable goods burned. Peckham is only a few seconds' flying time from the east end, and so any pilot who was a split second from or was picked up by the searchlights (which lots were), just dropped their bombs to lighten the aircraft in order to escape. This, thousands of homes in the surrounding suburbs were hit.

The fires in dockland burned for days.

"From this day on, London was bombed for 74 nights – and sometimes during the day – consecutively other than a couple of nights when the weather was too bad for air raids.

"

This meant going down to our shelter each night and staying there, except for trips to the toilet during quiet periods. We also had a couple who lived next door and used to come into our shelter, so there were six of us trying to sleep in this small area, and then next morning go to work, if it was still there.

One night, the houses behind us were hit. Luckily it was a small bomb, a 250 pounder, and it demolished the top half of both houses. When this happened, the dust from the explosion was so thick it could cause death to anyone trapped. After the explosions, we always went through the drill of calling out our neighbours' names to see if they escaped injury. Luckily they had all survived in their Anderson shelters.

"Not everyone had Anderson shelters, some had a shelter that used the kitchen table, turning it into a sort of cage. Not very good if the house was hit, because dust then became the killer.

"

After any raid, everyone had their favourite story to tell. Ours was of that night. After the bomb struck the houses behind us, we waited a while before coming out of the shelter to look around. Mum and Dad were outside when there was another explosion. Dad swung out his arm, telling us to get back into the shelter and accidentally hit Mum on the nose, which bled profusely. To stop the bleeding, he handed her a towel from the outside toilet, the towel we used to clean the toilet seat. I think that tale was told many times.

Surrey Docks burns during the Blitz. Image ©London Fire Brigade / Mary Evans Picture Library

An air raid is horrific, not just from the bombs but also the terrible noise of the anti-aircraft guns and the shrapnel that rains down afterwards. Also, lots of our own shells came down and exploded on contact with the ground.

Our worst fright came from the huge guns that were mounted on mobile railway platforms. The noise when these fired was terrifying, it was worse than hearing the screaming of a falling bomb. It was said at the time that 'if you hear the screaming of the bomb, then that one isn't meant for you'.

"It was during a night raid that I got my first official cigarette.

"

Dad and I were standing in the doorway of number 19, looking out to the street. Guns were firing, searchlights were probing the sky and it was nearly as bright as daytime. He rolled himself a cigarette and also one for me. I forget the exact words he said, but the cigarette was to give me some form of courage for what we were witnessing; the street had just been hit by some fire-bombs.

The fire-bombs had all been extinguished by the people who lived in the houses. We had been lucky, they had missed our house, but we all still had to be watchful. From the doorway we could see along the street, and the first sign of a glow in a window was a warning that a fire was starting. Everyone was looking out for their neighbours, the friendship and camaraderie during the Blitz was wonderful to behold. Adversity brings out the best in people.

Londoners filling sandbags in preparation for a raid. Image Mary Evans / Heinz Zinram Collection

The bombing of London caused widespread damage, but it wasn't enough to achieve Goering's goal of destroying British morale, or bringing England to her knees. Residents of London adapted to a new style of life, sleeping every night in a damp air raid shelter underground. The cold and damp brought on a 10% increase of tuberculosis, sometimes more dangerous than the raids themselves.

For myself and my mates it was a time of great adventure. Lots of children who had come back to London during the Phoney War were being evacuated again, with some of the richer families sending their children to Canada. On the 17th of September, a ship carrying 90 evacuees to Canada was sunk by the Germans in the Atlantic. Very few survived.

At the end of September, 1940, I left the paper shop in Nunhead and started a morning paper round with a newsagent nearer home. The woman who owned the shop was either a widow or her husband was in the forces, for I never saw him. She didn't have an Anderson shelter, and said that if a raid started when I was on my rounds I was to shelter in her hallway. On the morning of the 15th of October the siren sounded, so I finished deliveries in the street I was in and made my way back to the shop.

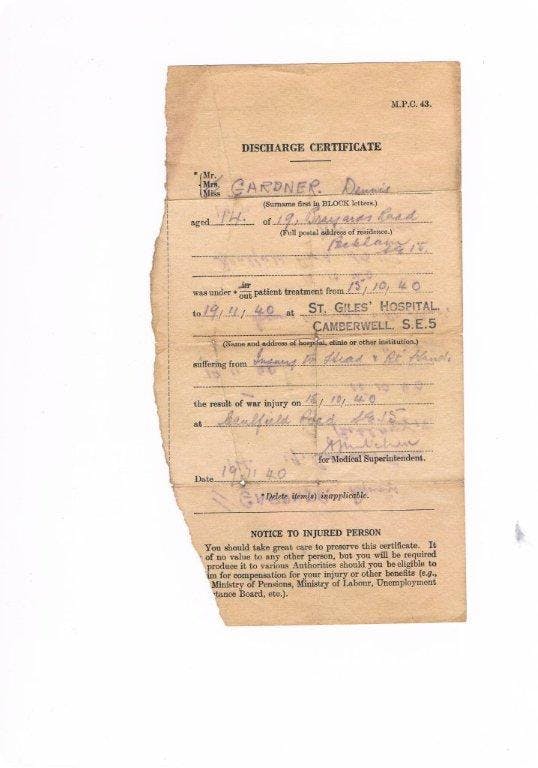

On the way I could see German aircraft in the sky and see the bombs falling from the planes. It was fascinating. I cycled towards the shop, and the next thing I remember was being put into an ambulance and being taken to St. Giles Hospital.

Denis' record at St. Giles after being injured during a bombing raid

A bomb had hit a house as I was cycling past. I had cuts on my head, as well as cuts and injuries to my wrist and arm.

"They told me afterwards that my greatest concern was whether my bike was OK.

"

It was most tragic at the hospital that morning. A food factory in Camberwell had been hit, and lots of young girls who worked there had lost their lives or were seriously injured.

I didn't go back to delivering newspapers. I was now the local hero, head bandaged and arm in a sling. A woman came up to me one day and told me she'd pulled a kerbstone off my head. The raids were still happening, but we were getting used to them and life had to go on. We had no counselling in those far off days, we called it internal fortitude then.

During this time, Mum would still have to go shopping and queue at each shop for meagre rations, often reaching the front of the queue to find the shop had sold out. I think in those days each housewife flirted with the butcher to try and get some rabbit or poultry that wasn't rationed.

In January 1941, aged just 14 years and 3 months old, I started work as an Instrument Maker's Improver, where I worked until I volunteered for the R.A.F. in early 1944.

Denis Spraying a Dakota, Karachi 1947 as a Leading Aircraftsman

I was called up on the 15th of May. My time in the R.A.F. was spent in India and Burma; I served there for two years, before being demobbed in December, 1947."

Related articles recommended for you

'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

History Hub

The history of the Barrow-in-Furness Shipyard

History Hub

Discover Warwickshire during World War Two

What's New?