From the Highlands to the world: Were your Scottish ancestors forced to relocate?

5-6 minute read

By Guest Author | October 6, 2021

Many corners of the world are rich in Scottish culture today. But our ancestors didn't always choose these places as home. Our partners at the Migration Museum explore the history of Scotland's Highland Clearances.

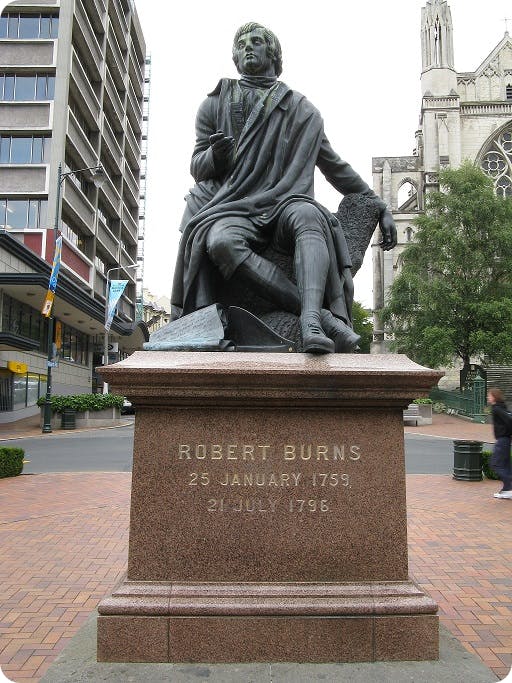

Before you stands a statue of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. Stuart Street is in front of you, while Prince Street and George Street branch out to your sides. In this city, you’ll also find Larnach Castle, bagpipes, traditional Highland dancers, malt whisky and haggis. If you haven’t guessed already, you’re in the centre of Dunedin, from the Scottish Gaelic Dùn Èideann, or Edinburgh. But you are not in Scotland. In fact, you are worlds away. Well, half a world away, to be exact.

If you dug a tunnel from Edinburgh, Scotland straight through the Earth, you would pop out in the South Pacific Ocean. The closest city with over 100,000 people? Dunedin, New Zealand.

A statue of Scottish poet Robert Burns located in The Octagon in Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand. Dunedin is known as the 'Edinburgh of the South'. © Thomas Beauchamp.

How did this city, on Maori land, become so infused with Scottish Highland culture? Especially considering that the Scottish Highlands are one of the least populated regions in Europe today? In order to make sense of any of this, we have to go back to the 18th century.

The Highland Clearances

At the start of the 18th century, around 30% of Scots lived in the Highlands and Islands. By the turn of the 20th century, this figure was just 8%. This was a result of the Highland Clearances, during which landowners evicted about 70,000 Highlanders and Islanders from their land over the course of 100 years.

Before the Clearances, Highland society was organised under the clan system, in which land was managed by crofts, or townships made up of about a hundred people each. These were subsistence-based joint tenancy farms that mixed arable and pastoral economies. Clanspeople looked to chiefs as landlords, protectors and kin, paying them rents and fighting for them in wars. However, by mid-century, Clan chiefs had begun responding to the Industrial Revolution’s growing capitalist markets. They concluded that the vast estates where clan members lived could be made more profitable under other uses, namely sheep grazing to meet Britain’s burgeoning demand for meat and wool.

By evicting Highlanders and moving them to the coasts to work in kelping and fishing industries, landowners believed that they could maximize the profit from their land while keeping a labour force.

Thus began mass evictions of generations of families from their ancestral homes, to be replaced by large-scale sheep farms and deer forests for the benefit of the elite.

While some Scots left voluntarily, others were forced into destitute conditions until they eventually left, and many more were evicted. Often, landowners burned and destroyed buildings so that they could not be reoccupied. Resistance to the evictions was routinely met with violence from the police or, at times, the army.

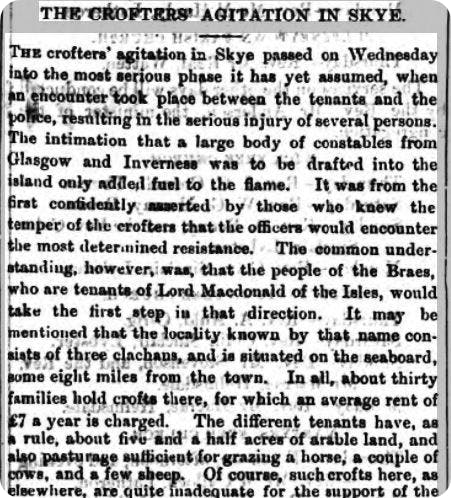

John o' Groat Journal, 27 April 1882. View full article.

The Battle of the Braes of 1882 provides an infamous case, in which 50 policemen battled crofters armed with sticks and stones on the Scottish island of Skye. Often, these protests were led by women, as they made up the majority of the population, while many men were either away at work, fighting the Napoleonic Wars, or dead.

Where did Scottish people migrate to?

Due to the loss of their land and these exploitative circumstances, many Scots emigrated to Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

Some left early on in search of a better life. Evicted crofters seeking employment in precarious coastal industries often fell into large amounts of debt. When coastal industries started failing, landlords agreed to forgive all debt if tenants emigrated, prompting even more to leave. Many others were coerced into being shipped as indentured servants to the expanding United States.

As the diaspora grew, Highland culture spread all over the world. This explains Dunedin, as well as the many other areas in the Commonwealth with large populations of people of Scottish heritage.

Town Hall and St Paul's Cathedral, Dunedin, New Zealand © Ulrich Lange, Dunedin, New Zealand.

However, while the global Highlander diaspora is sizeable, the Scottish Highlands today is largely uninhabited. Even the sheep have gone. In an ironic turn of fate, descendants of evicted Scots began sheep farms in Australia and New Zealand that grew to dominate the global market, prompting the closure of many remaining sheep farms in the Scottish Highlands.

What caused the Scottish Highland clearances?

In order to fully understand the Scottish Highland Clearances, we must look at the bigger picture. The Clearances were the result of many different factors. The combination of the Industrial Revolution, the expansion of the British Empire and the decline of clan power coincided with a change in the way that land was managed. There was a shift from smaller-scale land management systems which gave way to monopolised land ownership and the pursuit of profit.

Recent research published by Scottish historians Dr Iain MacKinnon and Dr Andrew Mackillop has revealed that wealth gained from slavery became very much connected to the Highland Clearances. Their research shows that at least half of the West Highlands and Islands, or almost 10% of the land of Scotland, was sold to slavery beneficiaries during the Clearances.

These lands were purchased with wealth from the slave trade, including money paid out by the British state compensating slaveowners for their “loss of property” after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

The destination of the many Scottish emigrants is also closely linked to the Empire. The countries that welcomed exiled Scots were options only because the British Empire had established settler colonies in these places. In fact, evicted Scottish immigrants assimilated into societies where they benefited from the mass displacement of local populations. Generations of Maori and other First Nations communities were evicted from their own ancestral lands.

Scots who emigrated to New Zealand were forced to assimilate into the dominant English culture, along with indigenous peoples. At home, the state aimed to pacify and assimilate Highlanders in part by banning Scottish traditional dress under the 1746 Act of Proscription. In New Zealand, the same processes were underway.

A legacy of culture

Today, reverberations of the Clearances can still be felt in the Highlands and their diaspora, both in lingering grief as well as celebration. Since the 1990s, there has been a movement in Sutherland, a county in the Scottish Highlands, to take down ‘the Mannie,’ a statue of George Granville Leveson-Gower, the first Duke of Sutherland. He was a brutal landowner who forcibly removed families and burned farmers’ homes.

Though this movement has not yet succeeded, feelings surrounding this historical injustice and pride in traditional Highland culture remain strong. The diaspora has played a large part in its preservation and celebration.

The Highland Games

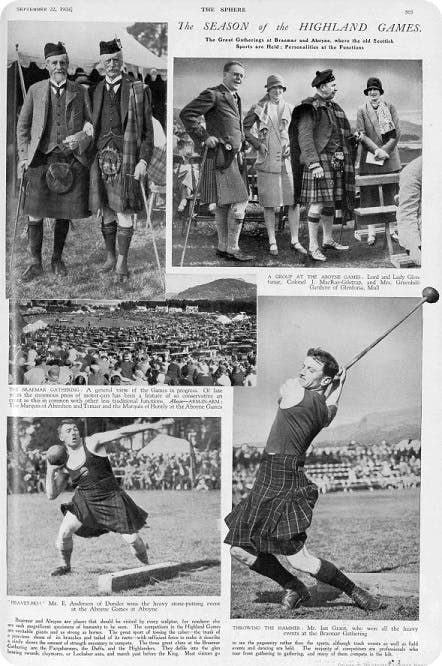

The Highland Games, which are held yearly, bring together tens of thousands of people from around the world to participate in piping, drumming, dancing, athletics and entertainment.

The Sphere, 22 September 1928. Read the full article.

Scottish-Americans participate in the Kirkin’ o’ the Tartan, and the Atlantic Gaelic Academy in Nova Scotia, Canada, is dedicated to the revival of the Gaelic tongue. Despite the many forces that united to banish Highland and Island people from their lands, their culture continues to survive, adapt and evolve.

Find out more about British emigration stories in Departures, a podcast from the Migration Museum exploring 400 years of emigration from Britain.

About the author

Anaïs Walsdorf is a French American historian and museum professional who is interested in histories of migration, colonialism, and museum collections. She has a Masters in Empires, Colonialism and Globalisation from the London School of Economics. Anaïs grew up in the Philippines but now lives in London, UK, where she has worked with the Migration Museum for several years, most recently as a researcher for the exhibition Departures. Other museum work includes visitor experience and engagement at Wellcome Collection. When she is not working or volunteering, Anaïs enjoys reading, laughing with friends, and enjoying nature- preferably all in the sunshine.

Related articles recommended for you

'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

History Hub

The history of the Barrow-in-Furness Shipyard

History Hub

Dig into your transatlantic roots this Findmypast Friday

What's New?