So, You've Found a Black Sheep in Your Family History...

3-4 minute read

By Cari Jolaoso | May 31, 2019

Embrace it. You're about to have the most interesting story at every dinner party from now on

Let's be honest. A lot of us start researching our family history to find pleasant surprises. Perhaps we've seen

Who Do You Think You Are?, and are secretly hoping to find a royal or a suffragette. Which is why it can come as a shock when Crime & Punishment records turn up something… well, a little darker.

What Skeletons Will You Uncover?

Disappointment, perhaps even shame, are normal reactions to finding a convicted criminal in your family tree - especially when looking at it through today's societal lens. However, it's important to remember that criminal justice pre-1900s was very different from the system we know today. With a rigid class system and very few opportunities for the poor, your black sheep probably contended with a set of circumstances that we'll never have to. For example, the problem that:

There was no Interest in Rehabilitation

Before the 18th century, nearly all punishments took place in public. From hangings and beheadings to vagrants being whipped back into their homes, to petty criminals being put in stocks. The attitude was that pain and humiliation should serve as a deterrent (and entertainment) for the rest of society.

Discover: William Calcraft: The Man who Hanged 450

From the 18th century, convicted criminals in Britain either faced extradition to America or Australia or were held in disused warships, known as

'hulks'. If your ancestor was imprisoned there and survived to have a family later, count them lucky. Living conditions in hulks were so bad, around a quarter of inmates died each year from disease or violence.

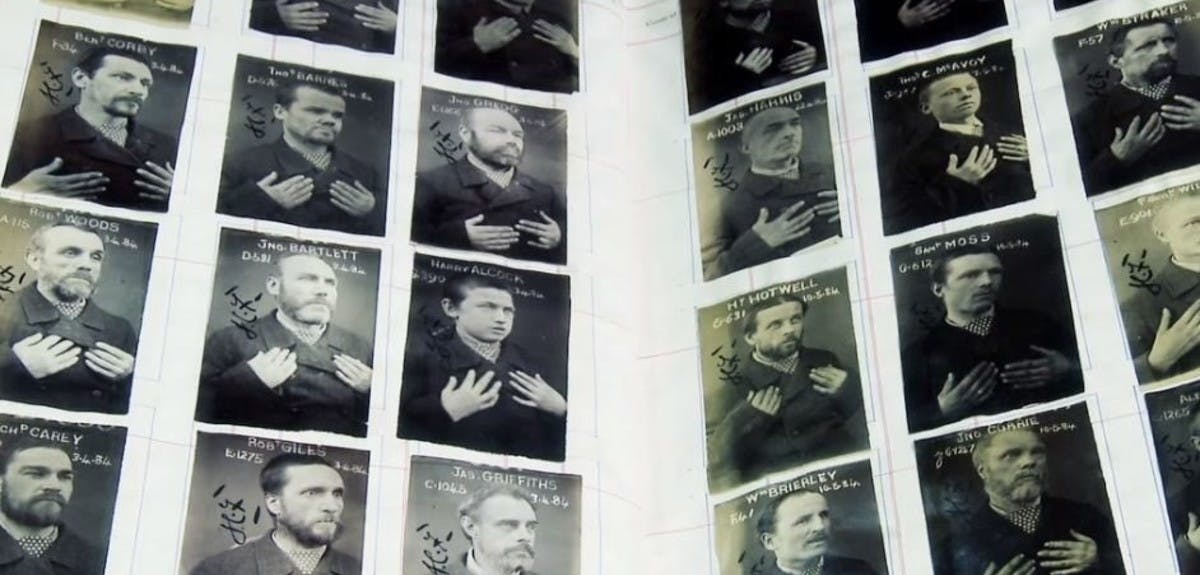

If your ancestor was sentenced from the mid-19th century, however, they may have fared slightly better. It was from this point that people began to acknowledge the overcrowding, death and low rehabilitation rates, and accept that the old methods weren't working. So from 1842, 90 more English prisons were built, which allowed inmates to have individual cells. However, it would take another century to introduce education and skills training, so prisoners had a chance of reintegrating after release.

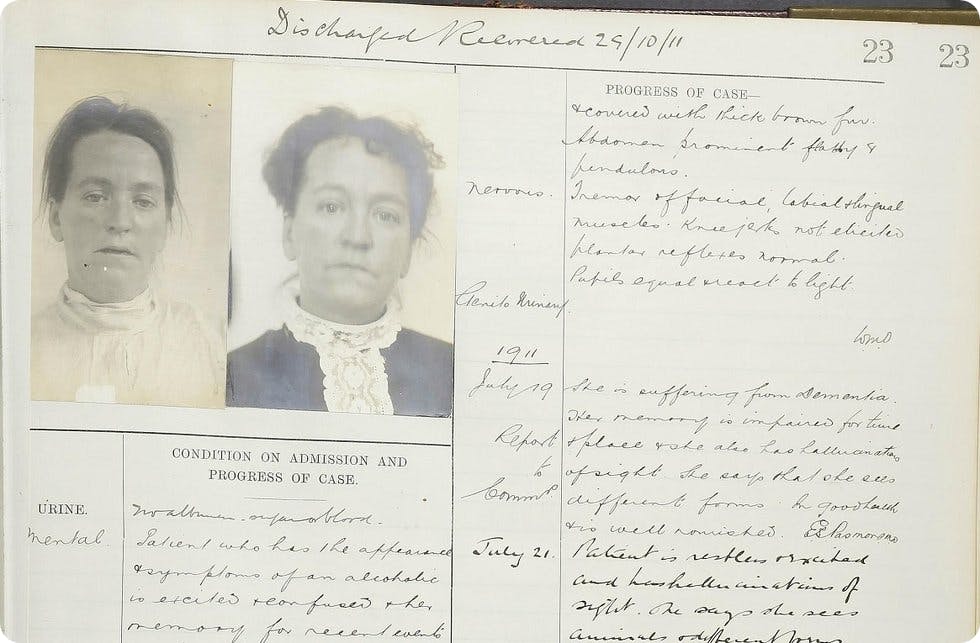

Mental Illness was Punished, not Treated

Explore: The Irish in Victoria's Mental Health Institutions

For example, in state institutions like the notorious

Bethlam Hospital in London (nicknamed 'bedlam'), treatment was carried out by non-licensed practitioners who ran the institutions for commercial gain with little regard for the inmates. As a result, patients were subjected to overcrowding, abuse, unhygienic conditions and disease.

Many of Findmypast's Bethlem records include photographs

From the 1820s, a flourish of newer institutions were built. But inmates still experienced brutal medical experiments with very little supervision. Even up to the 20th century, electric shock therapy and lobotomies - where part of a patient's brain is removed - were tested on inmates.

It took until 1959 for mental healthcare to improve under the NHS. From this point onwards, there was much more emphasis on treatment, self-managing conditions and community care.

Women Faced More Societal Punishment

A convicted female ancestor, who might be regarded as feisty or assertive today, would have faced extreme punishment in her time. Women who violated their subservient roles were heavily penalised by society and the law.

Search: Women's Criminal Records

In the middle ages, for example, women who disobeyed their husbands would be strapped to a cucking stool and submerged in a local river, or led around the town wearing a heavy iron cage for the head, and tongue irons if she'd quarrelled. More serious crimes, including adultery, would be punishable by hanging or burning.

In the 1700s, women who were were typically convicted for poverty-related crimes or sexual behaviour were sent to work as servants in America and Australia. Or, ironically, used as prostitutes or mistresses in the new world.

Learn: How to Find Female Ancestors

In 19th century England, correctional facilities and workhouses were introduced to confine less serious offenders, including penniless women and prostitutes. Women could also be sent to poorhouses or nunneries by men who wanted to punish disobedient behaviour.

In essence, the pre-20th-century world was not a kind place for anyone who was poor, had few life options or experienced mental health problems. Imprisonment was swift and harsh, and about retribution, not rehabilitation. We owe every black sheep in our family tree an immeasurable debt for enduring those circumstances long enough to continue a legacy, and eventually share their stories with us.

Are There Black Sheep Hiding in Your Family Tree?

Related articles recommended for you

Finding Eli: A granddaughter’s story

Discoveries

We found war veterans and healthcare workers within Keir Starmer's family tree

Discoveries

Marking 80 years since D-Day with updates to our World War 2 Allies Collection

What's New?