The shocking true story behind Wicked Little Letters

6-7 minute read

By Ellie Ayton | February 16, 2024

Historical comedy film Wicked Little Letters, starring Olivia Colman, Jessie Buckley, Timothy Spall, and a host of other leading British actors, will shock and surprise you. But did you know it's based on a true story that hit the 1920s press by storm?

And because we love a spot of local scandal, here's how the Littlehampton Letters Scandal, or the Seaside Mystery, played out in the real-life press - the tale is just as intriguing and just as shocking as the film it’s based on.

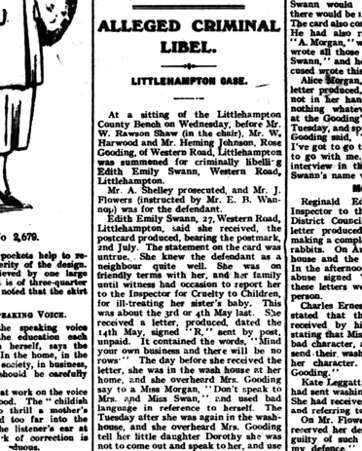

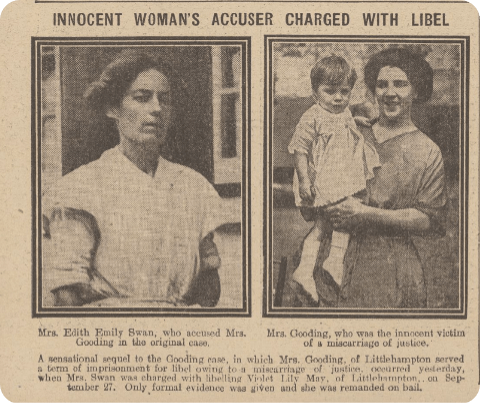

Our story begins in the English seaside town of Littlehampton in Sussex in late 1920, when Mrs Rose Gooding (played by Jessie Buckley in the film) was summoned to the Littlehampton County Bench for criminally libelling her neighbour, Edith Emily Swan (played by Olivia Colman).

The first mention of the scandal, found in the Bognor Regis Observer, 29 September 1920.

Edith told the court she and Rose had been on good terms until recently, when Edith reported Rose to the Inspector for Cruelty to Children for ‘ill-treating her sister’s baby’. There was also reportedly a row over their shared garden, and the Swans had become irritated with the loud arguments between Rose and her husband.

Then, on 14 May 1920, Edith received a postcard which read:

"You bloody old cow, mind your own business and there would be no rows – R"

More horrific poison-pen letters began to follow, filled with accusations and shocking language. Letters were also sent to the Swans’ laundry clients, warning them to stay away, and Edith’s brother Ernest had letters sent to his employer, accusing him of stealing.

Anyone associated with the Swans was targeted.

By March 1921, Rose was sent to prison for 12 months with hard labour. She appealed in April, protesting her innocence, but the appeal was dismissed.

Search for stories in our newspapers and publications

Explore millions of digitised pages of newspapers and other publications from our British and Irish collections, dating as far back as the 1700s.

So, the culprit was behind bars, and the people of Littlehampton could rest easy, knowing no more horrid letters would be sent.

This is where the plot thickens...

Where are Rose Gooding and Edith Swan in the 1921 Census?

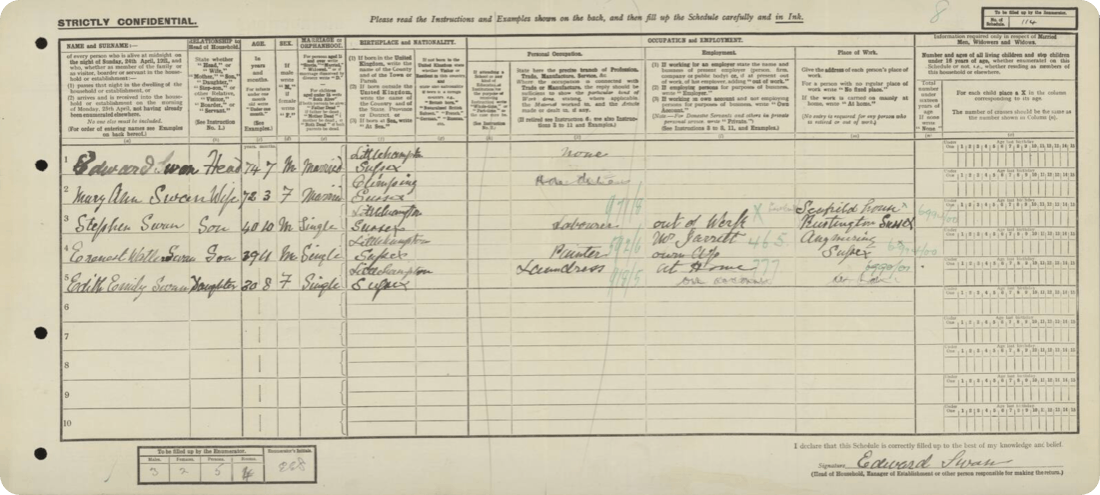

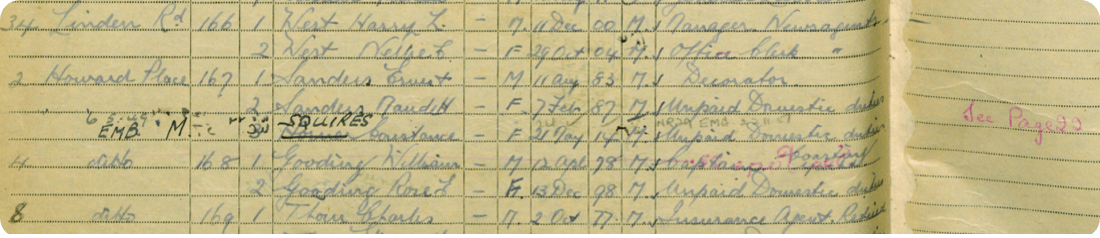

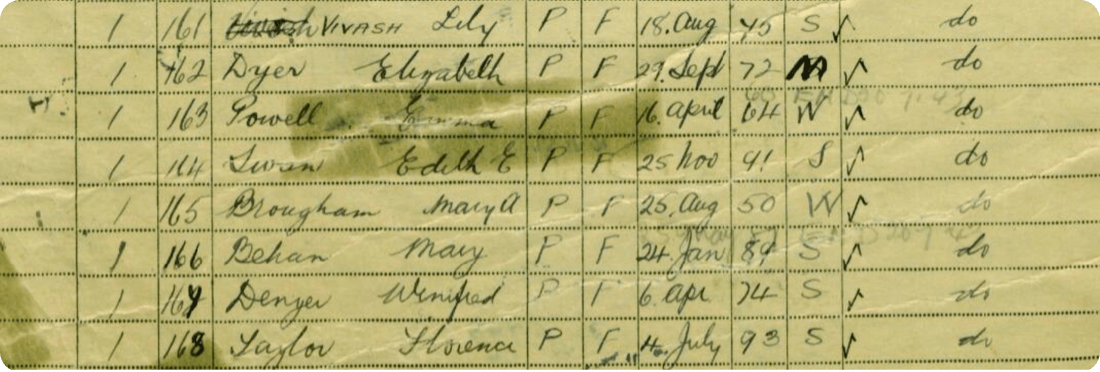

By sheer chance of timing, both Edith and Rose can be found on the 1921 Census, taken on 19 June 1921. Edith is with her parents, Edward and Mary Ann, and brothers Stephen and Ernest. Their address was 47 Western Road. We see that Edith is working as a laundress on her own account at home.

The Swan family in the 1921 Census.

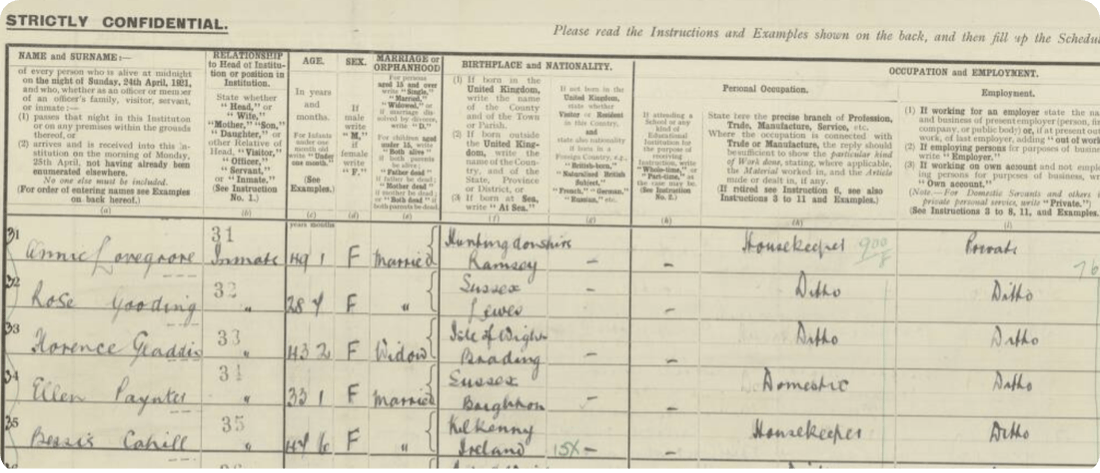

For Rose, on the other hand, her circumstances were entirely different. The snapshot in time that the census provides sees her serving her sentence at HM Prison Portsmouth. Her place of birth is Lewes - the real Rose wasn't Irish as she is in the film.

Rose Gooding in prison in the 1921 Census.

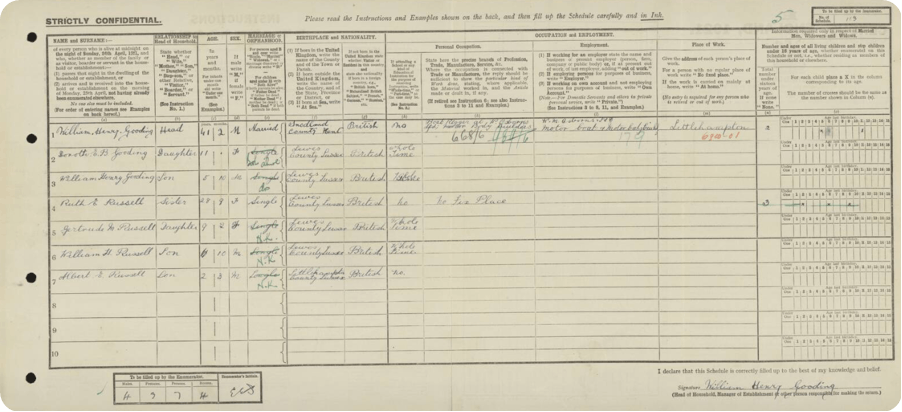

Next, if we look up Rose's husband, William Henry Gooding, we learn that the Swans and the Goodings were next-door neighbours – the Goodings house was number 45 Western Road. Also in the household are the Gooding children, Dorothy and William, and Rose’s sister Ruth Russell and her children, Gertrude, William, and Albert.

The Gooding household in the 1921 Census.

Dorothy was born Dorothy E B Russell in Lewes in 1909, before Rose’s marriage to William in 1913. In the 1911 Census, Rose was living with the infant Dorothy with her parents in Lewes.

The letters resume

Rose was freed soon a few months later. But when the letters and postcards resumed, Rose was sent back to prison. She appealed, but because both of her convictions had been a result of private prosecutions by Edith, neither the Court of Appeals nor the Director of Public Prosecutions could help.

Here’s where it gets interesting. While she was in prison, a notebook filled with obscenities in the same handwriting as the letters was found.

But if Rose was behind bars, then who was sending the letters?

Scotland Yard sent the eminent detective Inspector George Nicholls to investigate the matter, and he soon began to suspect that Edith Swan wasn’t being entirely honest. After examining Edith’s handwriting against that of the letters and notebook, he concluded that Edith had written the letters herself to frame Rose.

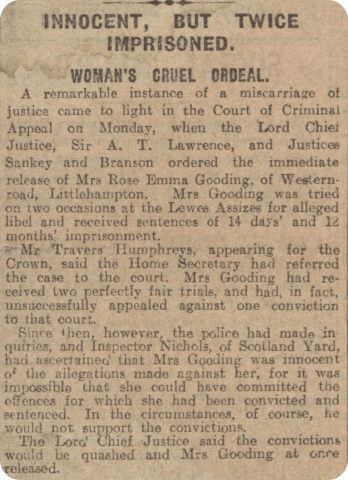

In July 1921, the Scotland Yard investigation had Rose’s second conviction quashed, resulting in her being freed and awarded £250 in compensation for being wrongly accused. Her prosecution was branded a 'miscarriage of justice' by the press.

Rose’s conviction found to be a ’miscarriage of justice’ in the Hull Daily Mail, 26 July 1921.

Then, the letters began again in earnest. Surely it couldn’t be Rose this time? Soon after, Edith was spotted leaving letters for another neighbour, and the case began to unravel.

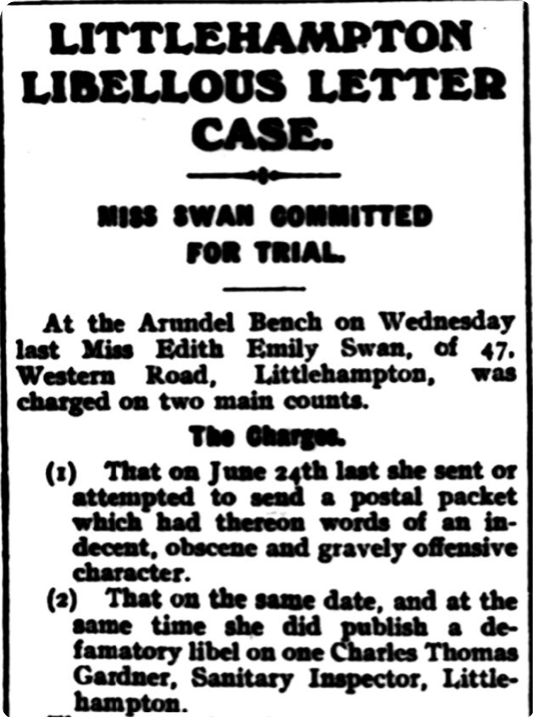

Edith Emily Swan, Rose's original accuser, appeared on trial in October 1921 for libel, but was acquitted in December - the jury could not believe such an upstanding, respectable woman could be responsible for such obscene language.

Edith’s first trial, Sunday Mirror, 23 October 1921.

The letters began again, more numerous and even more shocking than before. It was only after Scotland Yard arranged a sting operation to catch the culprit, using stamps marked with invisible ink to only be sold to Edith, was she caught red-handed.

Rose hadn’t sent the letters at all. It had been Edith all along, sending letters to herself, her family members, her family’s associates, other neighbours, all the while posing as her friend-turned-enemy, Rose Gooding.

Details of Edith’s trial appeared in The Bognor Observer and Visitor's List, 18 July 1923.

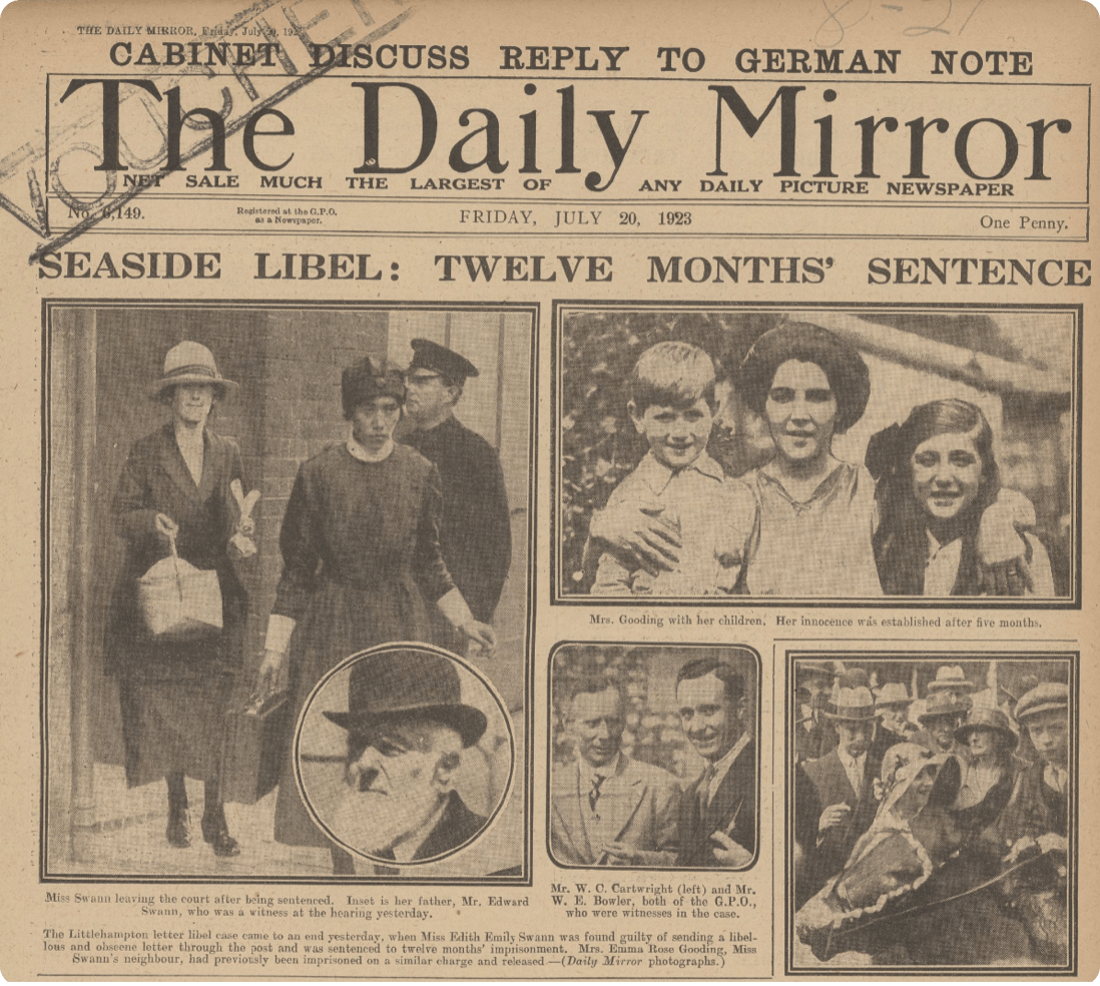

Then came the final trial in July 1923, where Edith was tried for an alleged attempt to send an obscene and libellous letter to the Littlehampton sanitary inspector.

Edith is seen leaving her second trial, pictured in the Daily Mirror, 20 July 1923.

She was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months' imprisonment. So, case closed?

What became of Edith and Rose?

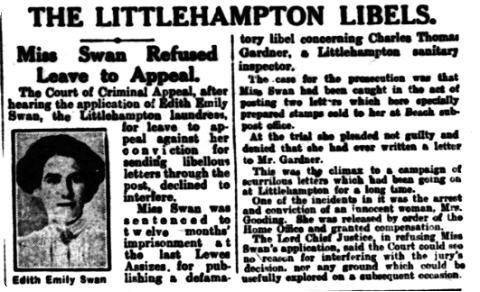

Edith attempted to appeal her conviction a month later, but it was quickly dismissed.

Edith’s appeal fails, found in Reynolds's Newspaper, 19 August 1923.

We don’t hear much of our leading ladies again until over a decade later. By 1939, Rose and her husband were still living in Littlehampton, who had hopefully put the scandal of the 1920s behind them.

Rose and her husband William in the 1939 Register. You can see the full record here.

It’s often been asked why Edith not only sent such letters to her neighbours, but also framed Rose for doing so. What was her motivation? It was speculated at the time of her trial whether Edith was in her right mind when she sent those letters.

There may be some truth in this. Sadly, by 1939 Edith was an 'incapacitated' patient, living at an institution in Worthing. She died in Worthing in 1959 aged 68.

Edith listed in the 1939 Register. You can view the full record here.

We wonder what lasting impact, if any, the Littlehampton Letters Scandal had on this sleepy coastal town.

You can discover more larger-than-life stories from history over at our History Hub.