The fascinating history of long haul travel from Britain & Ireland

5-6 minute read

By Alex Cox | September 4, 2020

The busiest ports. The most popular destinations. Who went where? We've delved into our travel records to bring you all the answers.

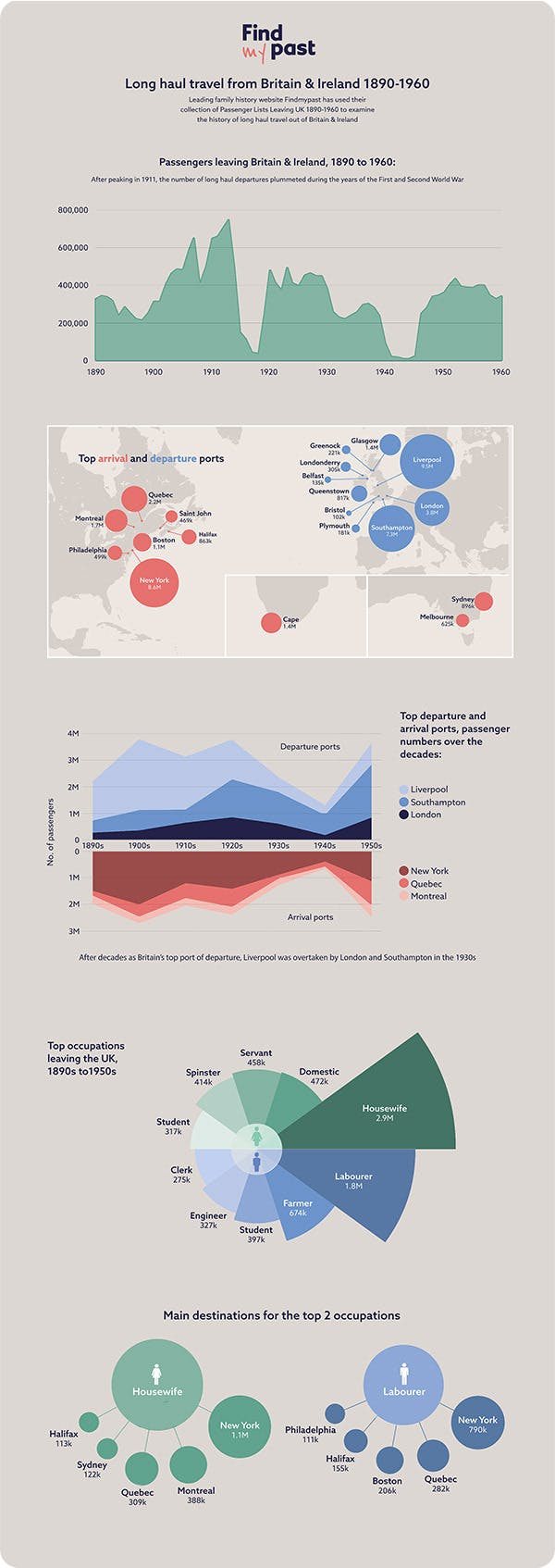

We have used our collection of Passenger Lists Leaving UK to analyse the history of long haul travel out of Britain and Ireland between 1890 and 1960, a period of major global change.

Passenger Lists Leaving UK 1890-1960 consists of more than 24 million transcripts and images of original documents held at The National Archives. The records cover long haul voyages to destinations outside Britain and Europe. Countries such as Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, South Africa and USA all feature strongly. But all continents are covered including ships sailing to Asia, the Caribbean, South America, West Africa, and even to remote oceanic destinations such as South Georgia Island.

These voyages often called en route at additional ports, including those in Europe, and any passengers disembarking at these stops are also included. Voyages from all British (English, Welsh and Scottish) ports, from all Irish ports before partition in 1921 and all Northern Irish ports after partition, are also covered.

Travel visualised

By analysing the details captured by these records (departure port, destination port, date of travel, gender and occupation) we have been able to shed new light on how typical voyages changed over time.

View the infographic in detail.

Global events and their impact

One thing that immediately leaps out is the incredible impact the World Wars had on international travel. While this may come as no surprise, the extent to which passenger numbers decreased is certainly striking.

As the "New World" continued to develop rapidly, larger numbers of British and Irish people began seeking better lives overseas. Records show that travel rates climbed throughout the early 1900s before peaking in 1913 with over 757,000 passengers departing.

This trend began to reverse dramatically the following year with the outbreak of the Great War. By 1916, the number of passengers departing from British and Irish ports had decreased six-fold to 113,508. The following year this number dropped even further to around 45,000 and by 1918, only 38,864 passengers were recorded, nearly a 20-fold decrease over just five years.

Painting by Willy Stöwer depicting a small British steamer, the Linda Blanche, being sunk by a German U-boat.

With war finally at an end, travel rates exploded in 1919 with over 247,000 departures. This number steadily increased throughout the roaring 20s before peaking in 1927.

By the 1930s, a combination of the Great Depression and the birth of commercial air travel meant that despite a gradual increase, departure rates never quite reached the same levels of the early 1910s.

As global tensions rose throughout the 1930s, the number of departures began to decrease again rapidly in 1938. As with the First World War, the Second World War put a virtual stop on overseas civilian travel as German U-boats patrolled the English Channel and North Atlantic. After significant yearly drops, departures fell to just over 10,000 in 1944, the lowest rate in the six decades covered by these records.

After Germany and her allies were defeated in 1945, the number of passengers leaving Britain and Ireland by sea once again rose sharply but, by the mid-1950s, commercial air travel was here to stay.

Britain's busiest ports

Analysis of the data has also revealed how after decades of topping the charts, Liverpool was suddenly overtaken as the top port of departure following the Second World War. Between 1890 and 1930, Liverpool's position as the UK's busiest port went unchallenged with more than twice the number departures recorded by its nearest competitors. This was not to last as"The Second City of the British Empire" was overtaken by Southampton in the 1940s and London in the 1950s.

This marked the dramatic decline of over a century of travel out of the city as, between 1830 and 1930, just under a quarter of the 40 million passengers who left Europe for the New World sailed from Liverpool, then the largest emigration port in the world.

George's Dock in Liverpool, 1897.

The records also reveal how Glasgow consistently remained Scotland's busiest port of departure, ranking fourth out of all ports in Britain and Ireland between 1900 and 1950.

Queenstown (renamed Cobh in 1920) on the coast of County Cork was also one of the top 5 ports of departure until the Irish Civil War and formation of the Irish Free State. By the 1930s, its place had been taken by Greenock in Scotland and by the 1940s, Tilbury in Essex had climbed to take its place.

New York, New York

During the six decades covered by these records, one city appears more than any other. Throughout its history, New York has served as the main port of entry for many US immigrants, and this is certainly reflected in the records. Year on year, without fail, New York took in more British and Irish travellers than any other port in the world.

European migrants arriving at Ellis Island, New York, in 1915.

In fact, the majority of long haul voyages appear to have been to the US during this period, highlighting the close historical and cultural ties Britain and Ireland share with the country. Boston and Philadelphia were also in the top five until the 1910s when the Canadian ports of Quebec, Halifax and Montreal overtook them.

By the 1920s, South Africa had climbed the ranks becoming the fourth most popular destination and Bombay made a brief appearance in the 1930s before rapidly falling out of favour (India achieved independence from Britain in 1947).

Australian ports also saw an increase in arrivals during the late 1940s and by the 1950s, both Sydney and Melbourne had made it into the top five.

Housewives and labourers

As passenger lists record occupations as well as dates and locations, we have also been able to examine the types of people that sailed out of Britain and Ireland. While students, engineers, merchants and "gentlemen" appear in large numbers, the majority of male travellers appear to have been blue-collar workers such as farmers, labourers, mechanics and miners.

A number of labour-intensive building projects took place in early 20th-century New York, including the construction of the Manhattan bridge between 1901 and 1912.

Given that women did not enter the workforce at the same rate as men until the second half of the 20th century, it is perhaps unsurprising that housewives formed the largest female contingent by far. Other female occupations that appear regularly include domestic servants, teachers, nurses and secretaries.

While it may also come as no surprise that New York was the top destination for both labourers and housewives, it must also be noted that skyscrapers began to appear in the city throughout the 1880s and 1890s. It is fair to assume that some of these labourers and their wives headed to the city to seek employment in its booming construction trade. Canada appears to have been the most popular destination for farmers, with large numbers travelling to Quebec, Montreal, Halifax and St John, while miners, engineers and merchants were largely seen travelling to South Africa.

Did your family leave the British Isles behind for a new life? Track their journeys and unearth their amazing stories in our vast collection of travel records. Then, share your discoveries using #FindmypastFeatured on social media.

Related articles recommended for you

Irish family history and minority religions in Ireland

History Hub

'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

History Hub

The history of the Barrow-in-Furness Shipyard

History Hub