Outlander: discover the brutal history behind the doomed Jacobite revolutions

5-6 minute read

By Jessie Ohara | March 23, 2022

With Outlander taking the world by storm from deep in the Scottish Highlands, explore how the Jacobite revolution truly began.

Outlander begins with Claire Randall, a British Army nurse, being transported back to 1743 after a trip to Inverness, where she finds herself in the centre of the Jacobite uprising. She tries to warn them against rebellion, knowing it was doomed. But why, exactly, were the Jacobite risings sure to fail?

How it all began...

There were some mutters of discontent across the country when James II and VII was due to become King in 1685. He was part of the 1.1% of England that practiced Catholicism, where the majority of the country practiced Protestantism or a Non-Conformist version. However, these mutters quickly abided to widespread support. He seemed to have strong tolerance policies, which appeased the Non-Conformists, and was unlikely to produce a male heir, after having been in a childless marriage for 11 years. His only daughter, Mary, was a Protestant - so the general consensus was that this would be a short interlude in a line of Protestant royalty. After all, this was the Divine Right of Kings - a monarch was chosen by God, not the people.

King James II and VII, circa 1690.

During his reign, he proved himself to be a politically messy monarch. While citizens were happy to disregard his own personal Catholicism, they were much less tolerant of Catholicism in general. When the English and Scottish parliaments refused to pass his tolerance measures for Roman Catholics, he tried to enforce them by royal decree, effectively discounting Parliamentary decisions entirely. This was also during a time in which King Louis XIV had outlawed Protestantism in France, forcing tens of thousands of Protestant refugees to escape religious persecution and seek a home in England. His religious toleration policies were, consequently, even less well received.

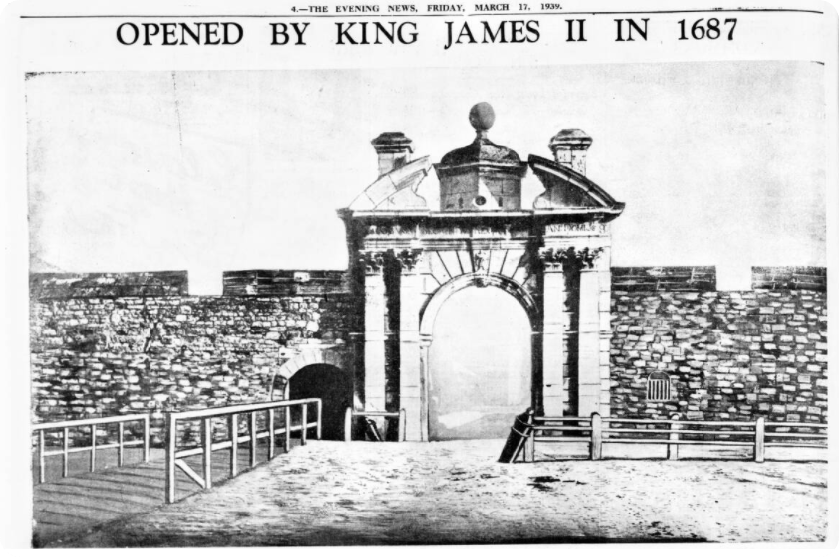

King James' Gate, opened in 1687, pictured in the Portsmouth Evening News, 1939.

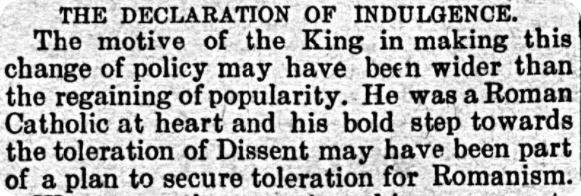

The King appointed many practicing Catholics in his highest ranks. When his Secretary of State - the Earl of Sunderland - began replacing more of his own officials with Catholics, James began to lose his Anglican support in droves. In 1687, he issued the Declaration of Indulgence, which negated the punishment of members of the Roman Catholic Church and Non-Conformists across the country, much to the citizen's chagrin. To further the popularity of the Declaration, he demanded it was then read out to every Anglican church. This didn't work, of course - instead, he offended and alienated many of the Anglican bishops against him.

The Widnes Examiner discussing James II and VII's Declaration of Indulgence, 1912.

He was convinced that he had enough support to continue with his toleration policies, specifically from the Irish, the Scottish, and the Protestant dissenters. When he again ordered the Declaration to be presented to Protestant churches, seven bishops - including the Archbishop of Canterbury - released a petition to the king requesting a reconsideration of his religious policies. Rather than reconsider, he had them prosecuted and imprisoned for libel. This caused widespread outrage, and is largely considered to be the first nail in his royal coffin.

The Protestant Association were still ordering lectures on the Trial of the Seven Bishops in 1848, as seen in the London Evening Standard.

When his wife, Queen Mary, gave birth to a son in June 1688 - something that was regarded as hugely unlikely at the beginning of his reign - it shifted the public opinion from outrage to revolt. It was clear now that his Protestant daughter would never take the throne, and instead it would be passed to a Roman Catholic descendant. In retaliation, his daughter Mary and her Protestant husband William, Prince of Orange, were invited by Anglican noblemen to invade, and so the Glorious Revolution of 1688 began. With many of his officials defecting, King James tried to flee. His first attempt was unsuccessful, but unwilling to make him a martyr of the Catholic cause, William allowed him to escape a second time. King James found refuge in Catholic France, and Mary and William were crowned joint monarchs by way of effective abdication.

The Divine Right of Kings?

Not everyone was happy about this, of course. The former king still had his supporters, particularly in Ireland and Scotland. James' abdication sparked a movement predominantly across Scotland - the Jacobites. While they religiously held a complex mix of ideas, they agreed on one common principle - the Divine Right of Kings. A monarch was appointed by God, the greatest force of all, and therefore a monarch could not be removed from their position, effectively making the reign of Queen Mary and King William illegitimate. Backed by King Louis of France - and, of course, the former King James - the Jacobites began their revolts.

Jacobite politics, described in The Scots Magazine, 1899.

Their first revolt in 1689 didn't go so well - the Jacobite numbers were limited, and when the British Army killed over 300 men, it was a huge loss. King William's fleet all but destroyed that of James II and VII, who had returned from France to fight, and a Jacobite defeat at Dunkeld disheartened many of the rebels.

However, Scottish prospects weren't looking great. There was very little economic growth, poor harvests, and King William's policies were proving unpopular. The Massacre of Glencoe, in which he killed the McDonalds of Glencoe for refusing to pledge allegiance to the Protestant crown, created a martyr for the Jacobite cause. William of Orange passed away, as did the former King James, leaving George I as King and James Francis as the claimant to the thrown. In 1715, the Battle of Sheriffmuir commenced. Jacobite forces were forced to withdraw due to loss of manpower, and so the second revolt also ended in failure for the rebels. James Francis didn't arrive in Scotland until after the battle, and simply returned to France, defeated.

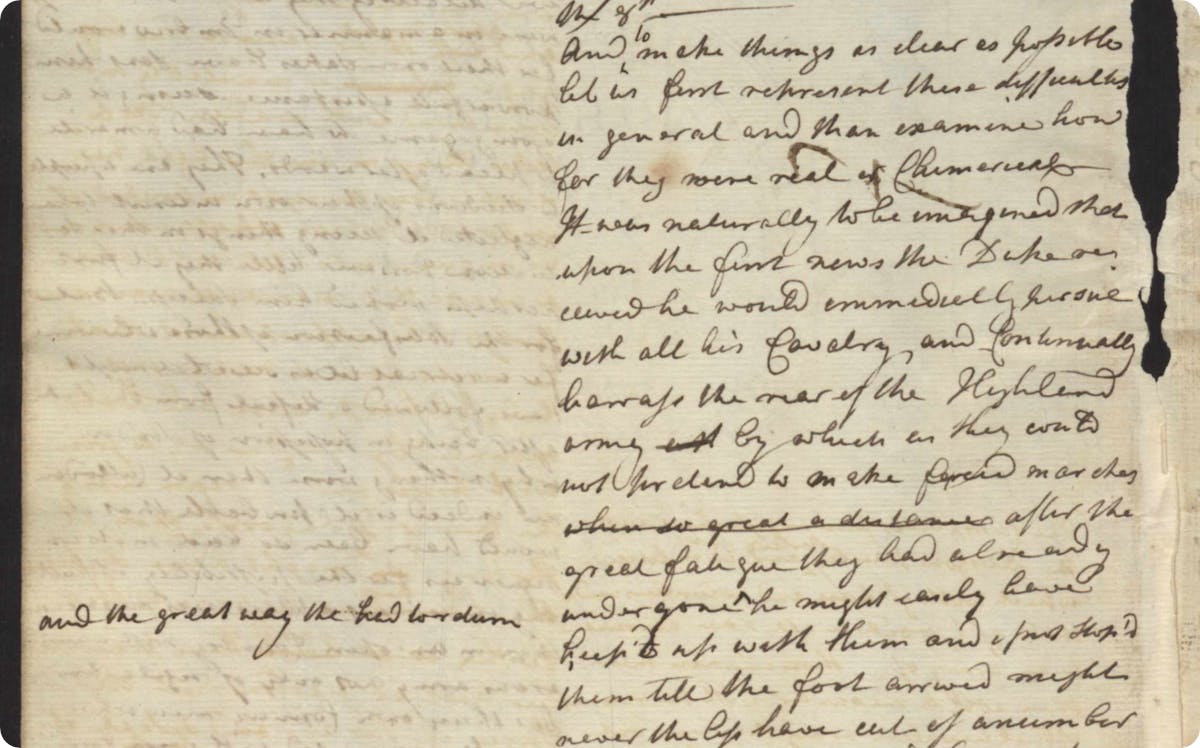

A snippet of our Jacobite Rebellion records, detailing the hopes of the army as they work through Calvary movement and intelligence.

The third revolt beginning in 1716 was backed by Spain, who were currently warring with Britain and Austria. Spanish forces thought it would distract the British forces enough to take back the land they had lost during the War of Spanish Succession. However, when a brutal storm in 1719 struck their 5,000 strong army at sea, only 300 survived. They reached Scotland and joined the 700 Jacobites remaining, but were defeated once again.

The Forty-Five

Imagine you're Claire Randall, aware of the repeated rebel defeats across Scotland, and you have travelled back in time to two years before the greatest war of the Jacobite uprisings - the final revolt of 1745.

Enter Charles Edward Stuart, a forceful 23-year-old prince, now known as Bonnie Prince Charlie. Designated the new leader of the rebellion, he pawned the famed Sobieska Rubies to pay for two warships. Though one was immediately decommissioned by the British and Hanoverian Army, he continued on to Scotland. This time, there was some success. Prince Charles Stuart and the remaining Jacobites managed to take Edinburgh - a huge victory - and other, smaller towns.

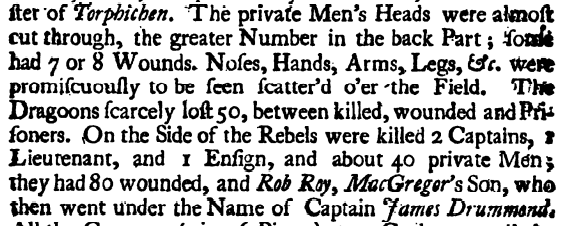

A snippet from our Jacobite Histories 1715-1745 collection, detailing a bloody scene at the taking of Edinburgh.

At this point, the Jacobite army was predominantly composed of impoverished and starving Scottish highlanders and Irish farmers. Charles Edward Stuart's council advised that he stop after Edinburgh, and allow the British and Hanoverian Army to continue their war on the continent. However, being the boisterous and enthusiastic 23 year old he was, Prince Charles decided to take his army forward to London. They made it as far as Derby before the Hanoverians descended, and forced them to retreat. They returned to Inverness, their strongest base, exhausted.

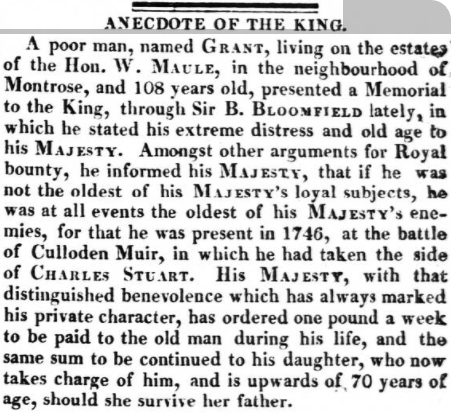

A elderly man is granted a weekly stipend after he was left in poverty following the Battle of Culloden Muir, Morning Post, 1822.

The British and Hanoverian armies weren't done there, though. Led by the Duke of Cumberland, they stormed up to Scotland, and effectively slaughtered any remaining Jacobite rebels at the bloody Battle of Culloden Muir. This ended Jacobite rebellion permanently. In an act known as the Highland Clearances, the Duke of Cumberland banned the bagpipes, the Gaelic language, and tartan, ending Scottish Highlander culture. This system lasted nearly a century. Prince Charles Stuart had fled and was nowhere to be found, the Jacobite rebellion was quashed, the Highlander culture demolished, and the few remaining Scottish and Irish rebels both impoverished and exhausted.

Now, again, imagine you are Claire Randall, and about to witness this occur. Imagine you'd fallen in love with a rebel highlander who was insisting on fighting his cause at the Battle of Culloden Muir. It's easy to see why she tried to warn them.

If Outlander has inspired you to research the Jacobite movement, make sure to browse our Jacobite Rebellions 1715 and 1745 collection, or discover war accounts and prisoner lists in our Jacobite Histories 1715-1745 index. Will you have an ancestor who fought on the bloody fields of Culloden?