Discover America's most trusted and treacherous in this week's release

4-5 minute read

By Jessie Ohara | July 1, 2022

Take a dive and revolutionise your American history with three pivotal American collections.

With 4 July just around the corner, we've released three collections that will become crucial to your American research. Whatever your heritage, discover history as it happened, including one of the most pivotal acts of rebellion seen in western society and its consequences.

Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

At the end of June in 1776, 56 men signed what is now known as the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration listed the 27 grievances against King George III from the 13 colonies. It was unanimously ratified on 4 July of the same year. By this time, Britain and the 13 colonies had been at war for over a year.

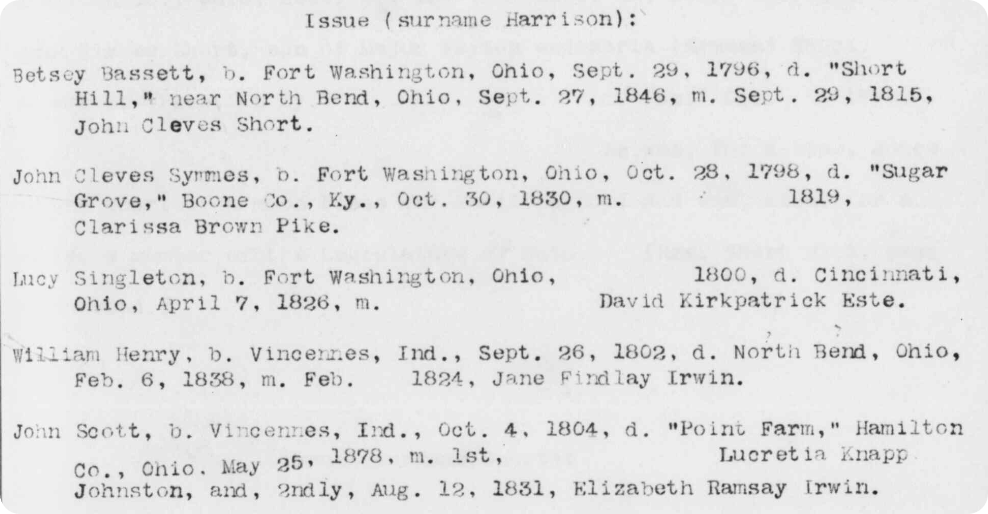

A snippet from this collection. View this record here.

Of these 56 men, the most famous is John Hancock, President of the Congress in 1776. It was also signed by John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Benjamin Harrison V was the father and great-grandfather to two other presidents, with Edward Rutledge being the youngest, and at age 70, Benjamin Franklin being the oldest. Most of these men had familial connections to the United Kingdom in one respect or another.

The Signing of the Declaration of Independence, by John Trumbull.

These records document the descendants of each of the Signers, following a traditional genealogical style, with the primary subject at the top of each page or section and their children listed below. Like most records from this time period, the information will vary from family to family. Where it was available, however, you may be able to find details around locations, dates, marriages and spouses, and more. The vast majority of these records will of course come from the United States, but many of these families had noted global connections, such as England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Europe, South America, or Australia.

Pennsylvania, Oaths of Allegiance Lists

Did your ancestor change the course of history by renouncing all loyalty to King George III and the Crown? Now's the time to find out.

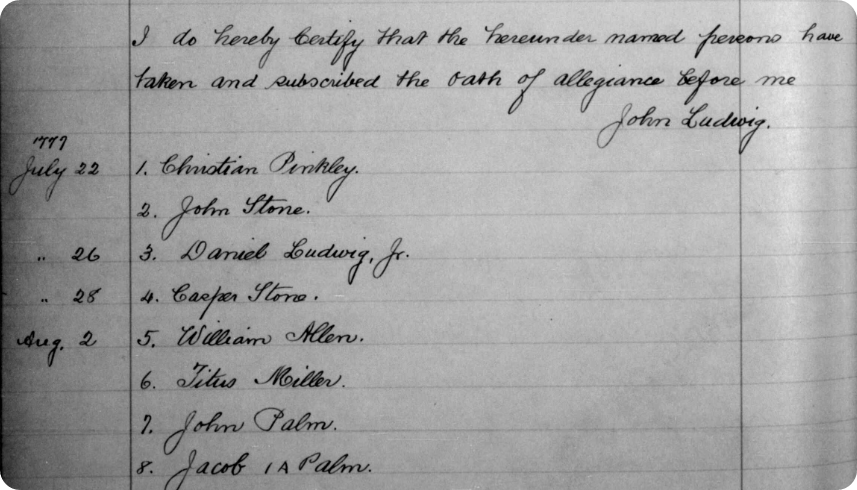

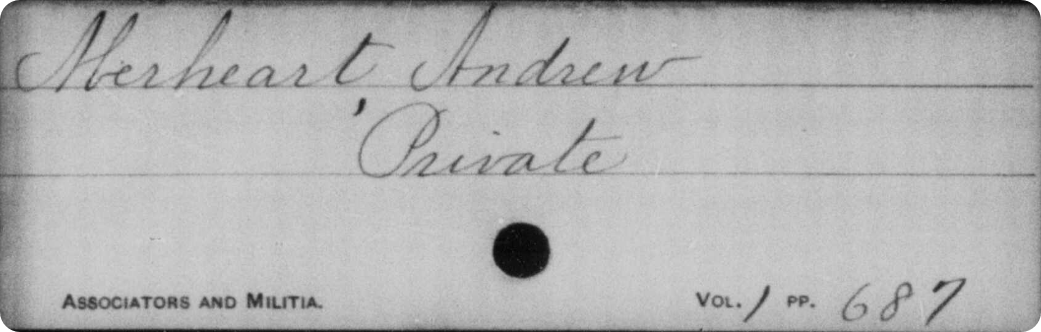

A snippet from this collection. View this record here.

Closely following the signing of the Declaration of Independence, all men over the age of 18 were required to subscribe to an oath that renounced all loyalty to the British monarchy and instead pledge allegiance to the new Continental Congress. These records were submitted by the Justice of the Peace to the Register of Deeds annually. Though they start in 1777, most of these records begin in 1778.

A Pledge of Allegiance marker in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

There are three key pieces of information that these records will give you: a name, a date, and a place. However, you would be remiss to assume that your ancestor was truly loyal to the Continental Congress, even if they signed the Oath of Allegiance. Those still in support of the British monarchy may have been motivated to sign for business reasons, pressure from the opposing side, or even been made to sign under duress. If you're researching your ancestors in this collection, you would benefit from studying the political climate year by year in newspapers and other sources, to obtain more nuance and detail.

Pennsylvania, American Revolution Patriot Militia Index

If your revolutionary ancestor was directly involved in the fighting of the war, then make sure to check out this collection and see if you can spot them. Not only will you discover that they were instrumental in the battle, but you'll find out exactly what their role was.

A snippet from this collection. View this record here.

This collection is composed of index cards for each individual, created from the four volumes of the Pennsylvania Militia, as found in the War of the Revolution: Battalions and Line, 1775 – 1783 (published in 1880) and Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution: Associated Battalions and Militia, 1775 – 1783 (published in 1890). During this period, the American colonies didn't have a standing army in place - the local militia was seen as a temporary solution for any quick issues that required protection. They didn't travel too far out of their local area, and they weren't originally intended to be a long-standing military force.

These records will tell you the name of the soldier, often their rank, and their type of involvement. This would either be “associators and militia” or “battalions and line”, with the former being a locally organised group of volunteers, and the latter being enlistees who were required for more long-term service.

Absorbed in American history?

You're in luck - in this Findmypast From Home session, our in-house expert and Research Specialist Jen Baldwin interviews Michael Troy, host of The American Revolution podcast.

Give it a watch for some fascinating insights into the way the British Army regulars viewed the Revolutionary War.

Scotland Monumental Inscriptions

A quick break from American history takes us across the sea to Scotland. We've added nearly 13,000 new monumental inscriptions to this collection, from Angus and Fife.

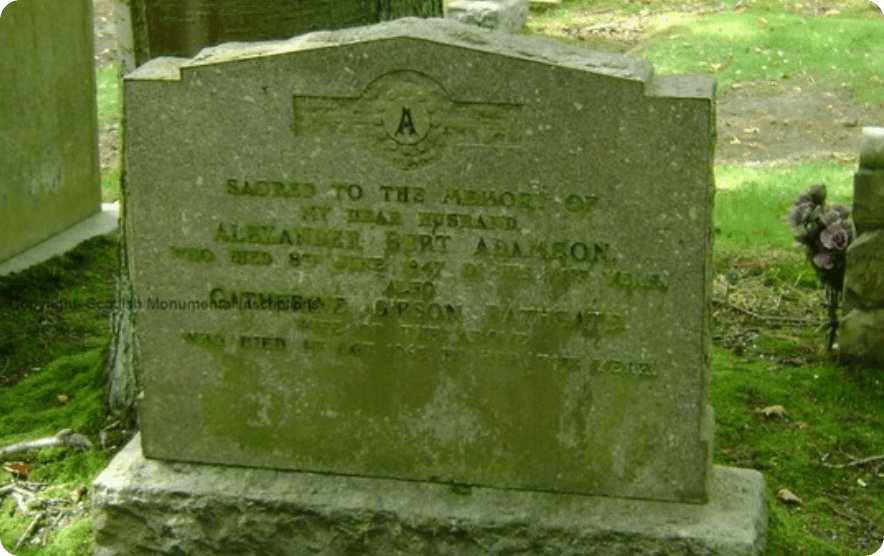

A monumental inscription from this collection. View this record here.

These records may give you a variety of information such as death year, names of others buried at the site, denomination, and the specific graveyard that they're buried in.

The news goes global

We hope you took a breather, because we're back to globetrotting. This week sees the release of our new American title, the Gazette of the United States, covering a post-Revolution period - so if you're looking to add some social and historical context to your discoveries this week, make sure to dive in and see what it has to offer.

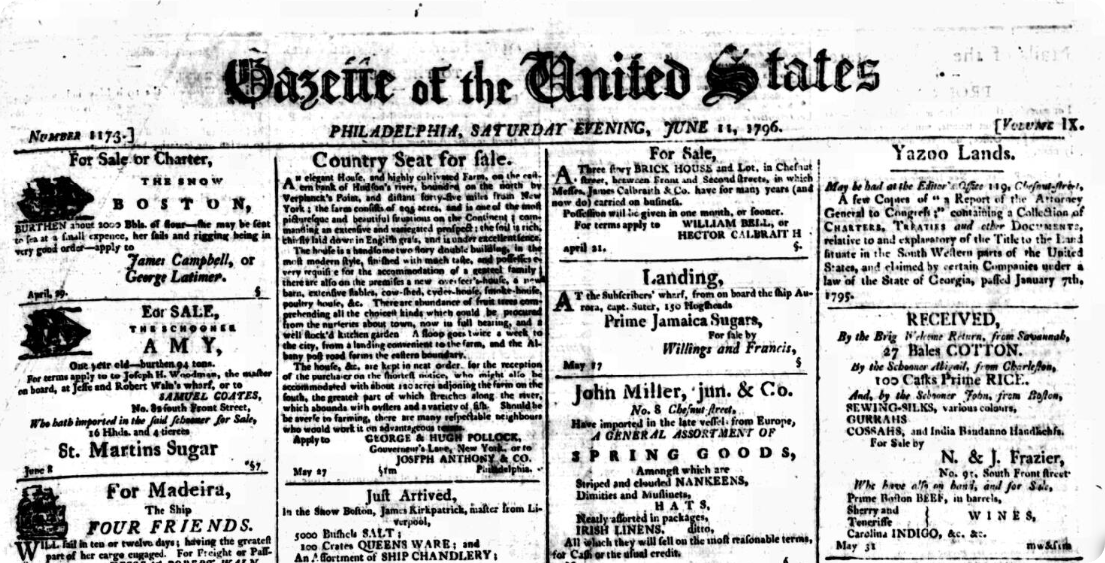

The title page of the Gazette of the United States, 1796.

As well as this, you'll also find Anglo-American title The Anglo-Americ]an Times and Canadian title The Ottawa Free Press. Alternatively, if the States and its surrounding areas aren't quite catching your attention, then worry not - we've also released two new Irish titles and one title from London. See below for a full rundown of new and updated titles this week.

New titles:

- Anglo-American Times, 1865-1896

- East Galway Democrat, 1913-1921, 1936, 1938-1949

- Gazette of the United States, 1789-1798, 1803

- Munster Tribune, 1955-1959, 1961-1962

- Ottawa Free Press, 1904-1909, 1911-1915

- Wallington & Carshalton Herald, 1882-1897

Updated titles:

- Brentwood Gazette, 1990

- Carmarthen Journal, 1998

- Colonial Standard, 1889

- Cork Weekly Examiner, 1897

- Derbyshire Times, 1919, 1927

- Dominica Chronicle, 1910

- Dominica Guardian, 1921

- Ellesmere Port Pioneer, 1990

- Harrow Observer, 1987

- Irvine Herald, 1989

- Llanelli Star, 1991

- Mirror (Trinidad & Tobago), 1901-1902, 1908, 1914-1915

- Stanmore Observer, 1991

- Westerham Herald, 1890

Have any questions? Just fancy a chat? Join us for Findmypast From Home on Facebook at 4pm UK time, where our experts discuss each new release and more.