Skip to content Operation Pied Piper: Evacuation in 1939 During World War 2, millions of vulnerable civilians left the country's centres of industry and shipping for the safety of the countryside Discover the evacuees in your family with the 1939 Register On the morning of Thursday, August 31st 1939, news outlets across Britain were all reporting the same thing. In the coming days, millions of vulnerable civilians would be evacuated from the country’s centres of industry and shipping for their own safety. The government feared aerial bombardment of cities and towns, something the world had so recently witnessed during the horror of the Spanish Civil War.

In the coming days, millions of vulnerable civilians would be evacuated from the country’s centres of industry and shipping for their own safety.

‘Evacuation Begins To-Morrow,’ were the words printed in large type across the front page of newspapers like the Express and Echo in Devon, which quoted the government announcement on evacuation: ‘It has been decided to start evacuation of the school-children, and other priority classes, as already arranged under the Government’s scheme, to-morrow, Friday September 1st. No one should conclude that this decision means war is now regarded as inevitable.’

September 1st – the day the evacuation began - was the day the Germany marched into Poland, triggering an agreement of mutual assistance between Poland and Britain. On the 2nd, Britain issued the Germans with an ultimatum: exit Poland, or a state of war will exist between us. On the 3rd, war was declared.

Evacuees from Bristol boarding a bus at Kingsbridge in Devon en route to their billets, 1940. Image: D2590 Crown Copyright Quite incredibly, within these first three days over 1.5 million civilians had been moved out of the cities. Codenamed Operation Pied Piper, this clearing of vulnerable individuals had been planned meticulously, and children, mothers, pregnant women, teachers, carers and disabled people had been – and continued to be – successfully evacuated in their droves.

Quite incredibly, within these first three days over 1.5 million civilians had been moved out of the cities

Arriving in rural areas was a shock for many of those evacuated, particularly the children. A lot of inner city children had never seen cows or pigs, had never been anywhere so green, and had never breathed air free of pollutants. Upon arrival, evacuated children would often be lined up in village halls, or against walls as potential foster families selected those evacuees that they could house, pointing children out and announcing ‘I’ll take that one’.

Some evacuees thrived in their temporarily adopted homes, having been placed with kind families in idyllic surroundings, far from the smoke-blackened terraces with which they were familiar, now under threat from aerial attack. Others, however, didn’t fare as well. Homesickness is a common theme when reading evacuee letters home, as well as confusion, bewilderment and often anger at being placed on a train and shipped to a mystery location, far away from their families.

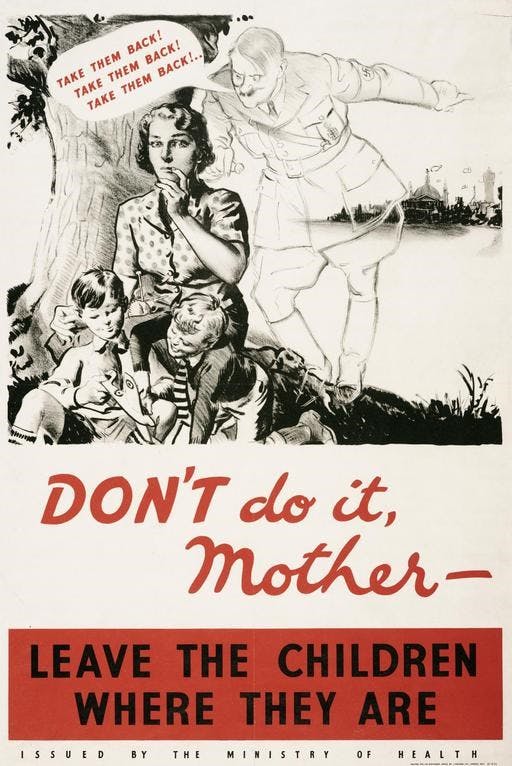

Children are Safer in the Country. LEAVE THEM THERE. Campaign urging parents not to bring their children back to the city during the Phoney War. Image: HMSO Crown Copyright This hints at the darker side of evacuation. While the majority enjoyed – or, at least, could easily tolerate – their time away, a significant proportion were mistreated or suffered abuse. The terrible reality was that for children and parents alike the only way to keep a child safe was to entrust him or her into the care of a total stranger.

The terrible reality was that for children and parents alike the only way to keep a child safe was to entrust him or her into the care of a total stranger.

Of course, not everyone eligible to be evacuated actually left the cities– some children were kept at home by parents and some vulnerable adults elected to stay at home. Within weeks, the effects on infrastructure were being felt. How, for example, could the inner cities cope with hundreds of its teachers being evacuated? How could rural communities cope with a sudden influx of children to educate? Similar issues arose around the country, in every area touched by evacuation. In many cases, evacuation placed a strain on rural communities that were ill-equipped to deal with it, and left vacuums in inner city areas that needed to be filled.

By the end of September, millions of people had been evacuated from the cities. The nation held its breath as residents of every major city kept their ears pricked for the drone of a German bomber, flying in from the coast to rain bombs on the rooftops of Britain’s conurbations. Shelters were dug, buildings were made light-proof and millions awaited the first air raid.

Further public information urging parents to leave their children in the countryside during the Phoney War. Image: HMSO Crown Copyright The wait lasted longer than anyone expected. Britain’s towns and cities remained untouched by German bombs for months. In fact, during this first stage of the war – the period which came to be known as the Phoney War - not very much happened at all. Fighting was limited and bombing non-existent, leading many of the parents of evacuees – against the advice of the government – began to bring their children home.

It wasn’t until the summer and autumn of 1940 that Germany invaded France, and the promised bombing raids arrived as The Blitz devastated British cities and ports like London, Hull, Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool and Manchester. A number of the parents who had brought their children home sparked a second, voluntary wave of evacuation, but many children remained at home throughout the war, having travelled back during the Phoney War. For those who stayed through the months of relative inactivity, Operation Pied Piper had helped to ensure that they were out of harm’s way for the duration of the war.

Main image: Arrival of the Evacuees in Luton, Bedfordshire. Stamps were issued for the Children to write home. Image: © The Wentworth Collection / Mary Evans Picture Library