Seaside escape or city break? Discover the incredible rise of tourism in the 1921 Census

4-5 minute read

By Brian Donovan | November 7, 2022

Our expert Brian Donovan dives into the rise of tourism, holidaymaking, and vacationing in 1920s England and Wales.

Out of the many weird and wonderful things we have discovered about the 1921 Census, perhaps one of the most unusual is the date it was taken - 19 June.

Censuses are normally taken in March or April, as these months are considered to be the most 'typical' of the normal flow of life. People are at work, the kids are in school, the harvest has not started, and most importantly the long evenings and better weather has not yet arrived. In short, most people are likely to be at home doing their normal activities.

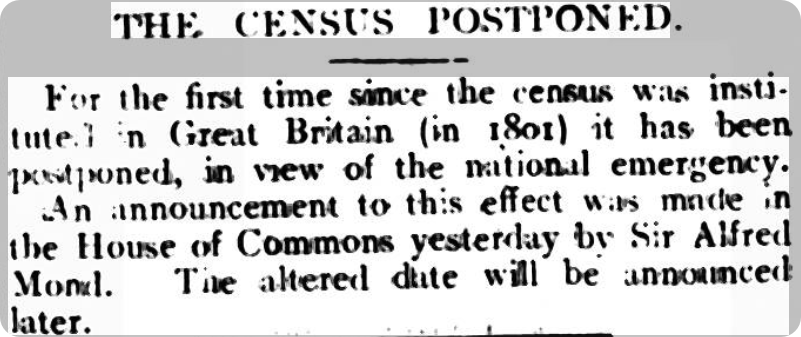

'The Census Postponed', The Millom Gazette, 15 April 1921.

The 1921 Census was scheduled to take place on 24 April, but for the first time in history, was postponed due to a fear of a general strike. Instead, the census was carried out on 19 June - the last date prior to the recognised industrial holiday season.

Despite this, it was an unusually warm and summery weekend, and the numbers of people who grabbed the opportunity to escape to the seaside were unexpectedly high. The census takers recognised this too, and were hugely irritated by the 'interruption of the chain of administrative processes, carefully prepared in advance'.

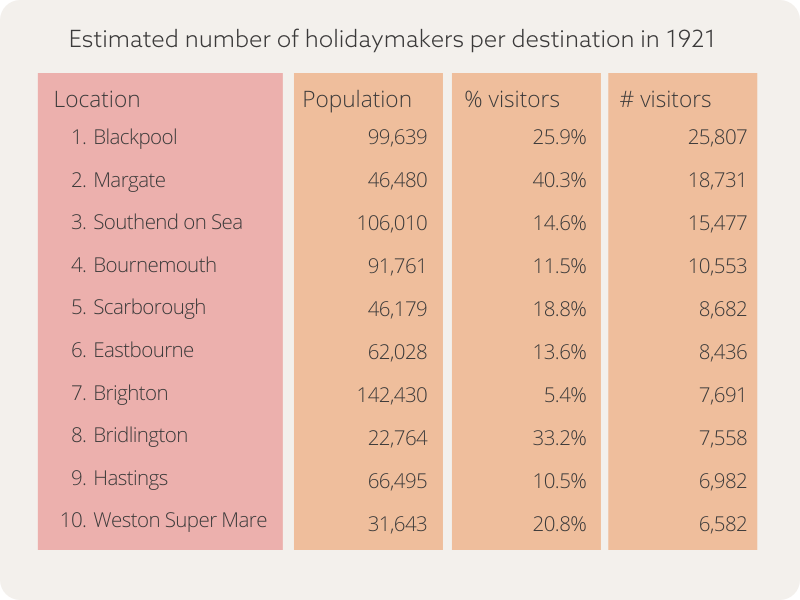

They also found that it had a serious impact on the census results, with 209 districts (out of 1,817) showing an increase of population of more than 3% and 92 with more than 10%. The estimates for places with the largest number of holidaymakers can be seen below.

The estimated number of holidaymakers per destination in 1921.

Even today these places all remain popular for vacations. Some locations had an incredibly high proportion of 'visitors' too. For example, more than 50% of those enumerated for Skegness, and over 40% from Barmouth, Shanklin and Margate were not normally resident there.

A family enjoying land-yachting on a beach in Skegness, 1925. Found in our Photo Collection.

So what does this mean for your research? Simply put, it means there’s a much higher chance the person you are trying to find will not be at home, but instead might be visiting somewhere else to enjoy the summer weather.

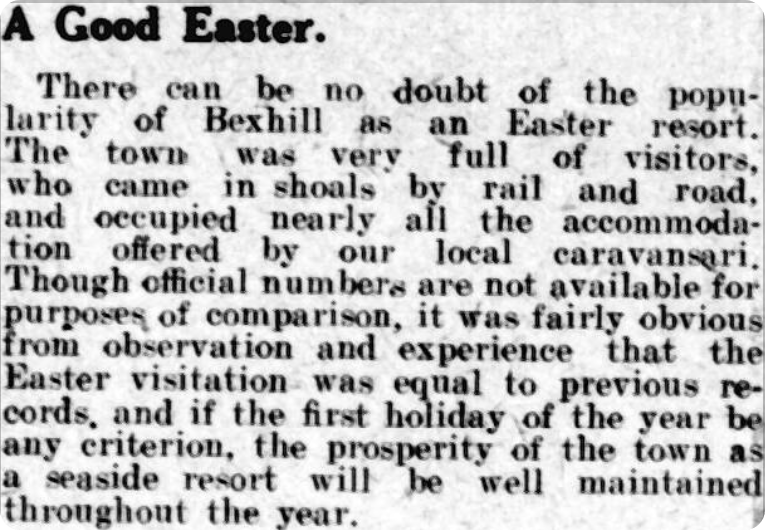

An article describing the popularity of Bexhill-On-Sea as a holiday destination, 1921, Bexhill-On-Sea Observer.

Holidaying or taking a vacation from work was growing in popularity in 1921. Except for a small number of bank holidays, most people were not entitled to paid leave until 1938. But weekend breaks or day trips were often possible for the bulk of the population because of cheap rail travel - and the evidence would suggest they took every opportunity they could.

A holiday advert found in The Graphic, 1921.

There was also the phenomenal growth of touring, and discovering the hidden charms of Britain. This had become all the more possible for the majority of people thanks to the improvement of local roads, and the availability of bicycles. The Macmillan Company began publishing the Highways & Byways series in 1899 and by 1921 had completed more than twenty publications in the series, which extended across the length and breadth of England, Scotland and Wales, with one publication on Normandy and another on Ireland. The inland town of Llandrindod Wells in Wales was a typical example, and 40% of those resident there in 1921 were visitors.

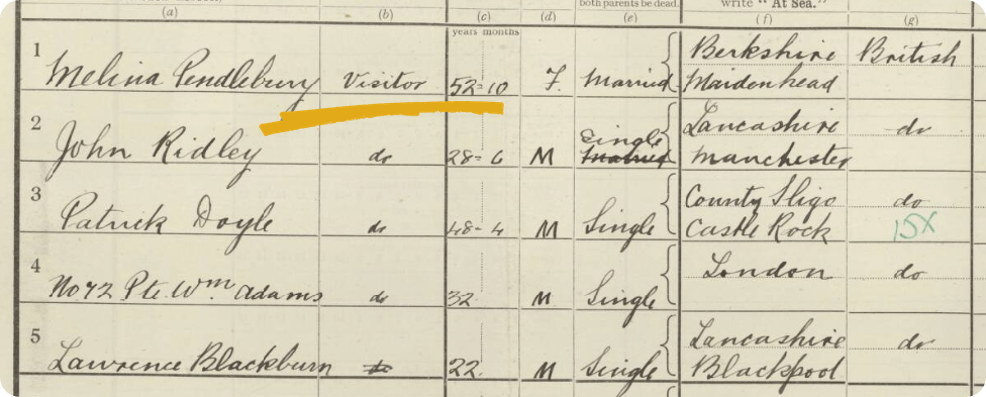

The challenge we have when looking at the 1921 Census is trying to determine when a person is travelling for leisure or for reasons such as work. The census enumerators used the term 'visitor' in the Relationship to Head of Household field as a designator for anyone who was not normally resident there, but its not always certain they were on holiday.

A 1921 Census return with eight people listed as visitors. View this record here.

For example, the eight people listed as 'visitors' in this return from Blackpool, pictured above, were all in the local police station that day and all had been 'found' sleeping rough. Were they homeless or maybe they were enjoying themselves too much?

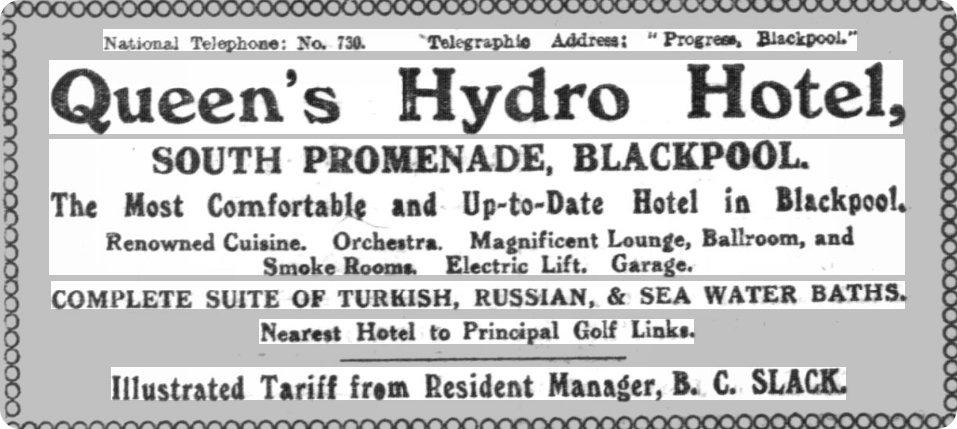

An advert for the Queen's Hydro Hotel, Blackpool, Sheffield Independent, 1916.

Typically you will find most easily recognisable holiday makers in hotels and guest houses. For example the famous Queen’s Hydro Hotel in Blackpool had 78 people listed in their return, of whom 23 were staff, including the Manager, Charles Ernest King, and the rest were visitors.

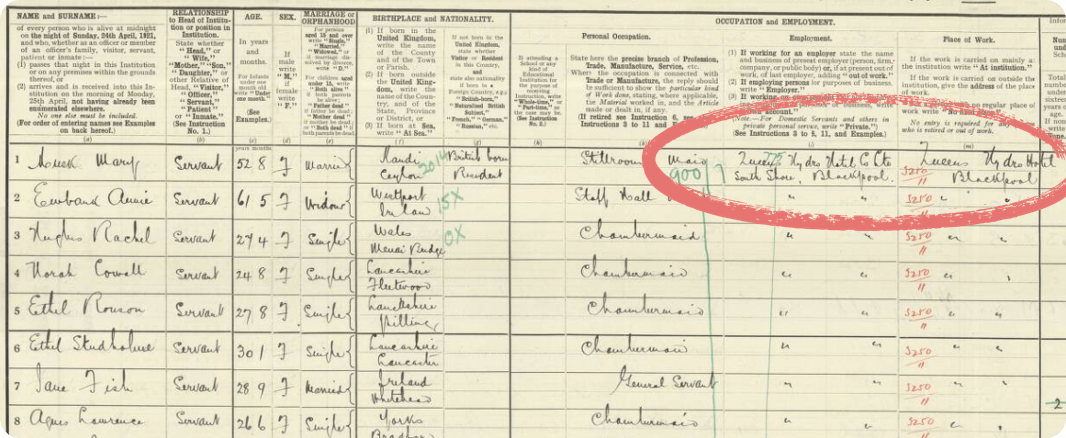

The Queen's Hydro Hotel's 1921 Census return. View the full record here.

Almost all of them were wealthy executives or lawyers, the sort of people who already received paid holidays.

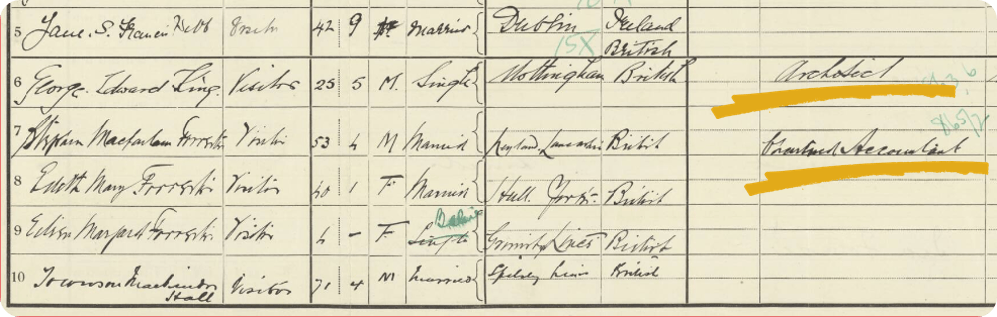

Similarly the 62 visitors at the famous Seacroft Hotel, Skegness, were accountants, architects, lecturers, managers, and business men.

The Seacroft Hotel's 1921 Census return. View this record here.

But holidaying wasn’t just limited to the middle classes any more. Young workers took the opportunity to get out of the cities. Margate, on the coast of Kent, has long been a popular seaside spot and a welcome escape from the smog of London.

Families on the beach of Margate, 1906, Francis Frith Collection.

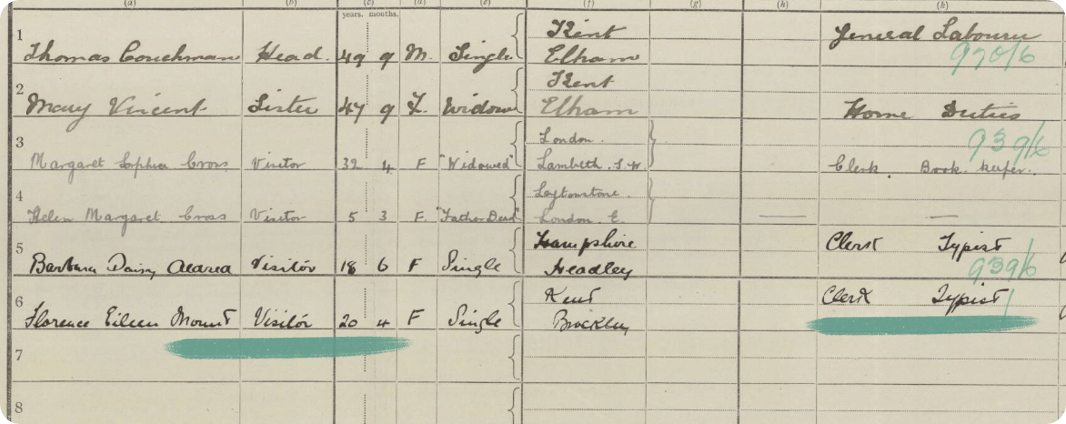

A good example is this return where a local labourer and his sister were taking guests in Westgate on Sea. There were four guests on 19 June, Margaret & Helen Cross, a lady recently widowed and her daughter, and Barbara Aldred & Florence Mount, two young typists working for the chocolate manufacturers FS Fry & Sons on Lever Street in Shoreditch.

A 1921 Census return with four visitors from London. View the full record here.

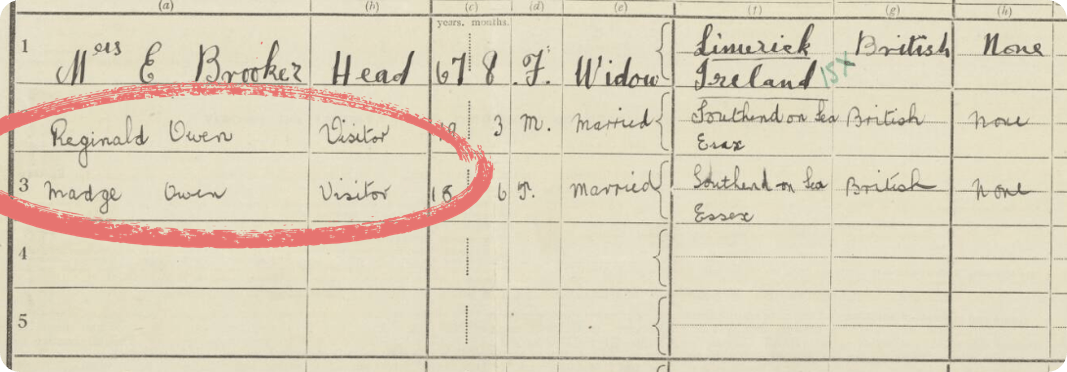

Sometimes a vacation could be very close indeed. Take this return in which Reginald and Madge Owen, aged 19 and 18, were recorded as visitors in the household of Mrs. E Brooker, a widow from Ireland, in her little house on Stromness Road in Southend on Sea.

Mrs E Brooker's 1921 Census return. View this record here.

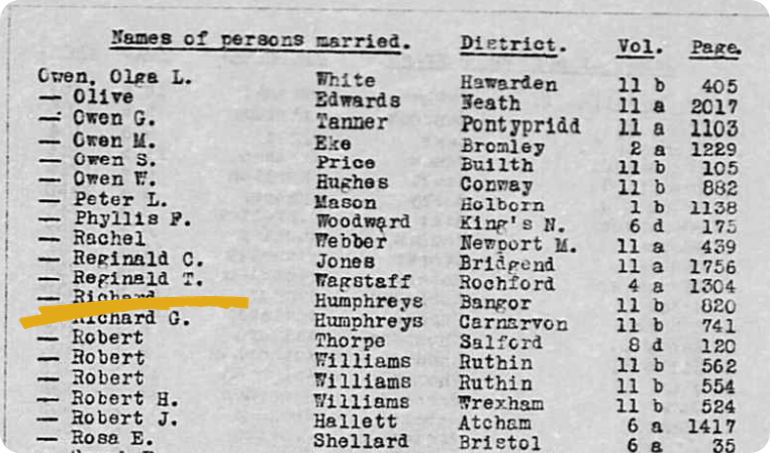

It had only one room we’re told, and the young couple were from the town. By searching our marriage records, we know they were newlyweds.

Reginald's marriage record. View this record here.

It was also a time when it was increasingly possible and likely for young women to travel on their own, especially the growing numbers of female college students as the male dominated universities started to open up.

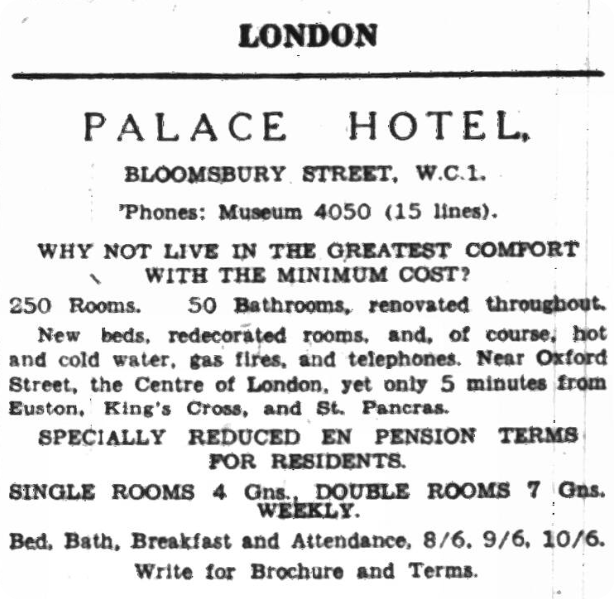

Margaret Mackay was one of these. A Scot, from the Dundee area, she was staying at the Palace Hotel on Bloomsbury Street, presumably taking a break from her studies at Cambridge.

An advertisment for the Palace Hotel, found in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1936.

Many of those recorded as visitors were really in convalescence, which is not surprising given the recent trauma of the First World War, like the Convalescent Institution at Robert’s Marine Mansions in Bexhill.

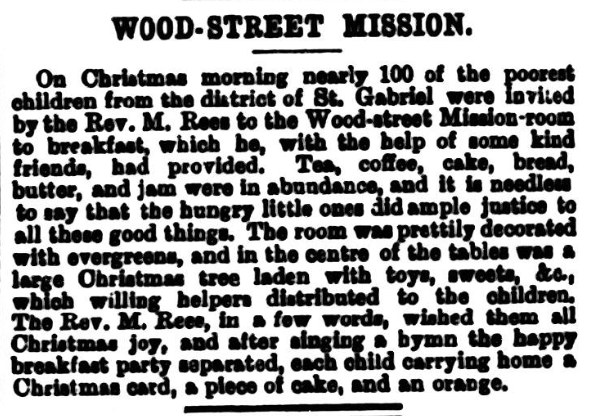

Charities also played a role in bringing the concept of holidaying to a broader audience. The extraordinary work of the Wood Street Mission is a case in point.

An article about a Christmas breakfast, by the Wood Street Mission, Walthamstow and Leyton Guardian, 1883.

This Methodist charity based in Salford paid for a camp in Blackpool to bring poor and destitute children from the slums of Manchester to the seaside. In 1921 they had 70 children at their holiday home.

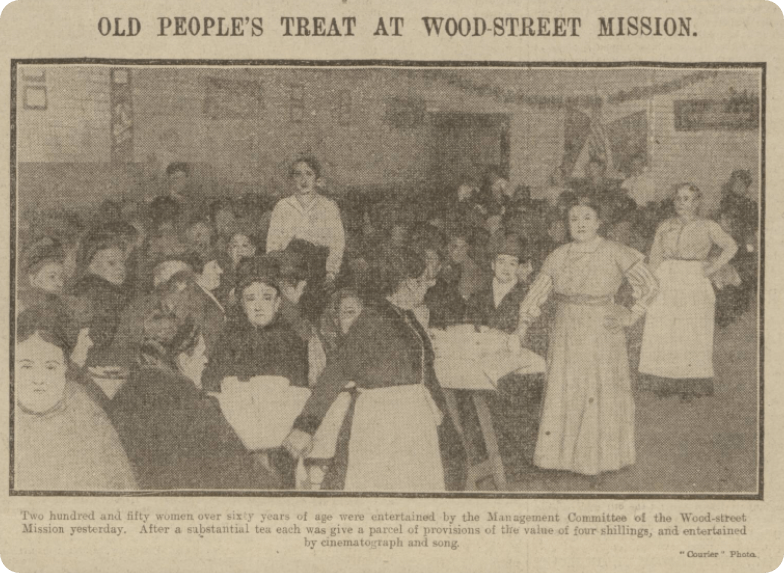

'Old people's treat at the Wood Street Mission', Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 1916.

So there are a myriad range of reasons why the person you are searching for could not be at home - they may have just been enjoying a summer holiday. It should remind us of the cardinal rule for researching family history in the census records. The census asks you where you are, not where do you live, and who are you with, not who is your family.

If you haven't found your ancestors yet, keep searching - who knows where in the 1921 Census they could turn up?